|

Psalters, and Bible Pages (Leafs) This page: Bibles to 1599 | Pg 2: Bibles 1600 to Present |

|

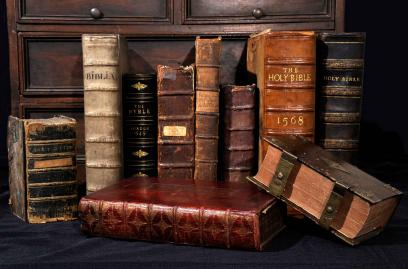

The antique and historic Bibles, Psalters, and pages (leafs) below are in my small but growing collection. They are NOT for sale, although I have listed the price I paid for reference purposes. Many of them represent important and/or notable versions or printings. About one-half are in English, while others are in Hebrew, Latin, Coptic, German, French, Italian, Swedish, Ge'ez, Arabic, Slavonic, &c. Many significant translations are represented such as Jerome, Wyclif, Tyndale, Coverdale, Geneva, Taverner, Bishops, Luther, KJV, Douay-Rheims, Latina, Le Sainte, and others. Also listed are psalters, books of illustrations, and church documents. Area of printed text is given in millimeters (h x w); page dimensions in inches (w x h). Click on any image for a super-sized image of the item.

The antique and historic Bibles, Psalters, and pages (leafs) below are in my small but growing collection. They are NOT for sale, although I have listed the price I paid for reference purposes. Many of them represent important and/or notable versions or printings. About one-half are in English, while others are in Hebrew, Latin, Coptic, German, French, Italian, Swedish, Ge'ez, Arabic, Slavonic, &c. Many significant translations are represented such as Jerome, Wyclif, Tyndale, Coverdale, Geneva, Taverner, Bishops, Luther, KJV, Douay-Rheims, Latina, Le Sainte, and others. Also listed are psalters, books of illustrations, and church documents. Area of printed text is given in millimeters (h x w); page dimensions in inches (w x h). Click on any image for a super-sized image of the item.No single work has been printed more often than the Bible. Because they are so common, most Bibles have no significant monetary value. Certain editions are collectible, especially older ones, important translations, and notable printings. However, from a collection like this one can get a sense of both the history of the Bible and the history of Christianity. Have fun exploring it!

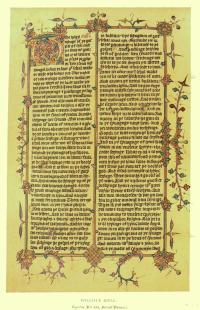

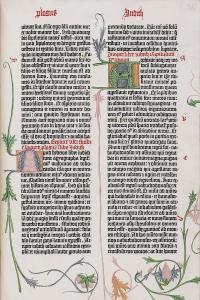

Replica leaf, c.1400, Wycliffe New Testament, English, Acts 1:1-22. Printed early 1900s?, 6.5" x 9.8" ($5.35)

Replica leaf, c.1400, Wycliffe New Testament, English, Acts 1:1-22. Printed early 1900s?, 6.5" x 9.8" ($5.35)The two Wyclif (Wycliffe) Bible translations in middle English were actually done by Lollard (“mutterer”) followers of John Wyclif, not by Wyclif himself. Both were translated from the Latin Vulgate. The first in the early 1380s was attributed to Nicholas of Hereford and others. It painstakingly preserved the Latin word order, which sometimes obscured the meaning in English. The second, completed in 1395 by John Purvey (like this one), had a more idiomatic and readable text. Despite Church attempts to burn and destroy them and condemnation by Canterbury Archbishop Arundel in 1408, about 250 Wyclif Bibles survived into the 1400s.

This is a roughly half-size replica of the 11.4" x 17.3" original. It had two columns of 46 lines; written in a large and rather thick hand. Initial letters of chapters are illuminated, and the first pages of books (like this one) surrounded with borders in gold and colors.

Click here for a readable text version of this page in a Roman typeface.

Click here for the British Museum reference for this page, Egerton Mss 617-618.

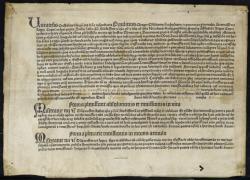

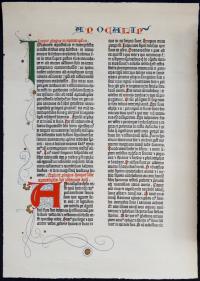

Replica, 1454 Papal Indulgence, Latin, Original printed by Johannes Gutenberg, 7.8" x 10.8"

Replica, 1454 Papal Indulgence, Latin, Original printed by Johannes Gutenberg, 7.8" x 10.8"Indulgences were (and are) awarded by the Roman Catholic Church as a remission of sin, earned either by prayer or, especially in the later Middle Ages, through a donation of money. Letters of indulgence took the form of ready-made receipts leaving an empty space for the name of the purchaser, who was to take it to a father confessor as proof of having obtained the right to the forgiveness of sins.

Gutenberg printed indulgences at the request of Nicolaus Cusanus, the prominent German cardinal, as early as 1452, none of which have survived. Most surviving copies are from 1454 and 1455 and are called the “Mainz Indulgences.” Gutenberg printed these letters on vellum, with dimensions varying between 6.2" x 9.3" and 7.8" x 10.8".

Gutenberg printed indulgences at the request of Nicolaus Cusanus, the prominent German cardinal, as early as 1452, none of which have survived. Most surviving copies are from 1454 and 1455 and are called the “Mainz Indulgences.” Gutenberg printed these letters on vellum, with dimensions varying between 6.2" x 9.3" and 7.8" x 10.8".This indulgence (several versions shown) printed by Gutenberg in 1455 was used by Paulinus Chappe (his name is on the top line), a Cypriot nobleman and the pope’s representative, to raise money to defend Cyprus against a Turkish invasion.

For the printer, indulgences meant cash, paid for by the Church, much needed for other printing ventures. For the Church it meant a rationalization of an otherwise labor-intensive bureaucratic procedure: thousands of identical letters of indulgence could be required during a single visit to a town. Compared with writing them out by hand, they could now be produced at much reduced cost. Printing provided an efficient solution to a bureaucratic problem.

We do not know how many copies of this indulgence were printed. By the end of the century, one indulgence was said to have been printed in 142,950 copies.

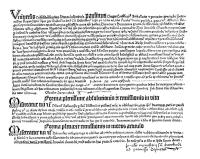

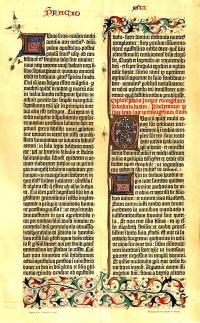

Replica leaf, c.1454 Gutenberg Bible, Latin, Book of Judith, Giclée print by Renfield, 7.3" x 11.0" image size on 9.5" x 13.0" sheet. Original size was 11.7" x 16.4". ($13.98)

Replica leaf, c.1454 Gutenberg Bible, Latin, Book of Judith, Giclée print by Renfield, 7.3" x 11.0" image size on 9.5" x 13.0" sheet. Original size was 11.7" x 16.4". ($13.98)The first item printed on Gutenberg’s new printing press in 1454 was a Papal indulgence—that is, a document that certified the bearer had asked or paid for and received from the church some remission of time in Purgatory.

In the fall of 1454, Gutenberg exhibited sample pages of his Bible at a Frankfurt trade fair. He reported that he had buyers for all of the 180 copies of the Bible then in production. The text is the revised Latin Vulgate translation produced in the early 1200s at the University of Paris. All copies were printed in folio format for public reading and were printed on both vellum and paper. Each Bible was usually bound in two volumes.

This replica leaf has the opening page of the Book of Judith, in which the titular character delivers her people from an Assyrian army by inveigling her way into the general’s tent and lopping off his head. Found in the apocrypha, the story of Judith—a virtuous femme fatale—has been the inspiration of artists for centuries.

Printed in black letter, two columns, 42 lines per column. Initial capitals and beautiful marginal illumination were added by hand on the original pages.

Replica leaf, c.1454 Gutenberg Bible, Latin, Revelation 1, Gutenberg Museum, Mainz. 304 x 195, 11.7" x 16.4" ($18.00)

Replica leaf, c.1454 Gutenberg Bible, Latin, Revelation 1, Gutenberg Museum, Mainz. 304 x 195, 11.7" x 16.4" ($18.00)The Gutenberg Bible has no title page, page numbers, or any other feature to distinguish it from a manuscript (hand lettered) edition, which Johannes Gutenberg strongly desired.

In a very short time his invention of mass-quantity printing caused a revolution in the European publishing world. By the end of the 15th century, printing shops operating in some 250 cities and towns across Europe greatly accelerated distribution of the Bible in both Latin and vernacular languages. The second-known printed Bible, published in Strasbourg in 1466, is a German translation.

This leaf includes scripture from Rev 1:8: “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End,” a call to live by faith. Printed in black letter, two columns, 42 lines per column in the traditional way on a replica Gutenberg printing press on an individual sheet of handmade linen paper. The colored heading, capitals, and borders in vivid colors with 24-carat gold leaf were added by hand.

Replica leaf, c.1454 Gutenberg Bible, Latin, Scripture verses?, Chromolithograph (1886), Bibliographischen Institut Leipzig. 326 x 195, 8.7" x 15.5". ($8.55)

Replica leaf, c.1454 Gutenberg Bible, Latin, Scripture verses?, Chromolithograph (1886), Bibliographischen Institut Leipzig. 326 x 195, 8.7" x 15.5". ($8.55)Before Gutenberg, culture and knowledge were reserved for the educated and wealthy; after Gutenberg, it was made available to anyone who could read. At the center of a seismic change in literacy, education, politics, and economics was the Bible—printing made it widely available and translation into vernacular languages made it more easily read and understood.

Chromolithography was invented by Alois Senefelder in 1797. In the process, separate limestones serve as a carrier of each color. In chromolithography, up to 14 colors are printed in order to achieve the various tonal gradations. Unlike today, mineral colors are employed whose brilliance and lightfastness is unsurpassed. These colors do not fade, and even after more than 100 years, they have a unique, bright luminosity. Only the paper is subjected to damage from light, yellowing slowly at the edges, with some spotting due to moisture unavoidable.

Although replica pages differ in size and format, all of the first printing of the Gutenberg Bible were on pages measuring about 11.7" x 16.3" with a text block of 304 x 195 mm.

Printed in black letter, two columns, 42 lines per column. Initial capitals and beautiful marginal illumination were added by hand on the original pages.

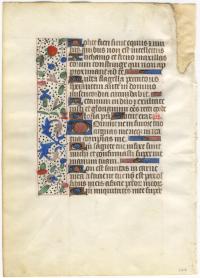

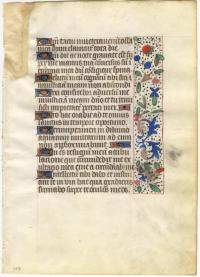

Illuminated vellum leaf, c. 1460 Book of Hours. From Bruges. 125 x 103 mm, 6.0" x 8.6" ($163.31)

Illuminated vellum leaf, c. 1460 Book of Hours. From Bruges. 125 x 103 mm, 6.0" x 8.6" ($163.31)The Book of Hours is a Christian devotional book popular in the Middle Ages. It is the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript. Like every manuscript, each manuscript book of hours is unique in one way or another, but most contain a similar collection of texts, prayers and psalms, often with appropriate decorations, for Christian devotion.

Books of Hours were usually written in Latin, although there are many entirely or partially written in vernacular European languages, especially Dutch. Thousands were produced in the 1300-1500s and tens of thousands have survived to the present day in libraries and private collections throughout the world.

The typical book of hours is an abbreviated form of the breviary which contained the Divine Office recited in monasteries. It was developed for lay people who wished to incorporate elements of monasticism into their devotional life. Reciting the hours typically centered upon the reading of a number of psalms and other prayers every day.

Produced in Bruges, the main center of Flemish book production. Written by hand in dark brown ink in a gothic face, 21 lines, with illumination and gold leaf on initial capitals. Vellum repaired at upper corner at binding edge.

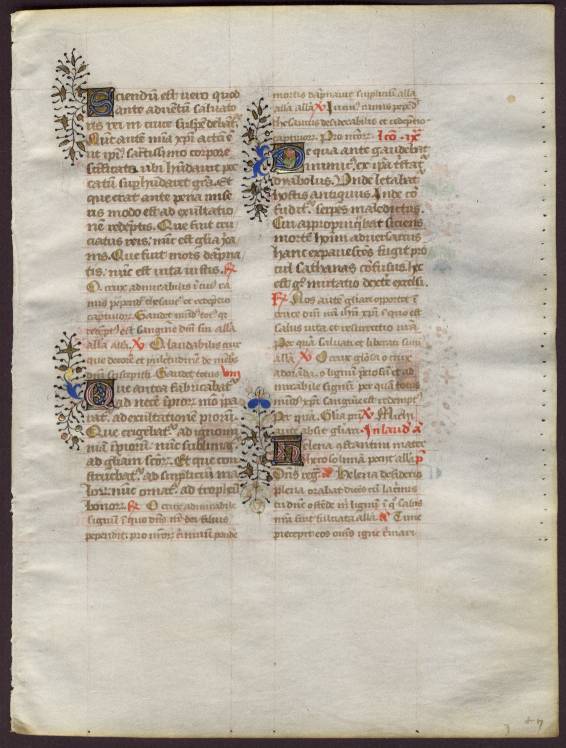

Incunable Leaf, 1474 Liturgical Text. Latin. Produced by hand in a French Scriptorium. 115 x 85 mm, 5.4" x 7.4" ($83.00)

Incunable Leaf, 1474 Liturgical Text. Latin. Produced by hand in a French Scriptorium. 115 x 85 mm, 5.4" x 7.4" ($83.00)A masterfully illuminated, very decorative manuscript leaf from a medieval liturgical text, dated by the scribe on a colophon leaf. The initials are meticulously executed with colorful decorations of vines and flowers and highlights in gold. Lettered on very fine, almost translucent vellum with minor traces of use and minimal evidence of storage or aging.

Right margin has 32 pinholes marking spacing for each spacing line, which are inscribed in light brown. Four pinholes are at the bottom for vertical lines to delineate the columns. Main text (possibly scripture?) consists of 31 lines of text in a brownish ink, approx 10 pt, with explanations in 8 pt. Each main block of text opens with a gold and blue letter about 2½ lines high.

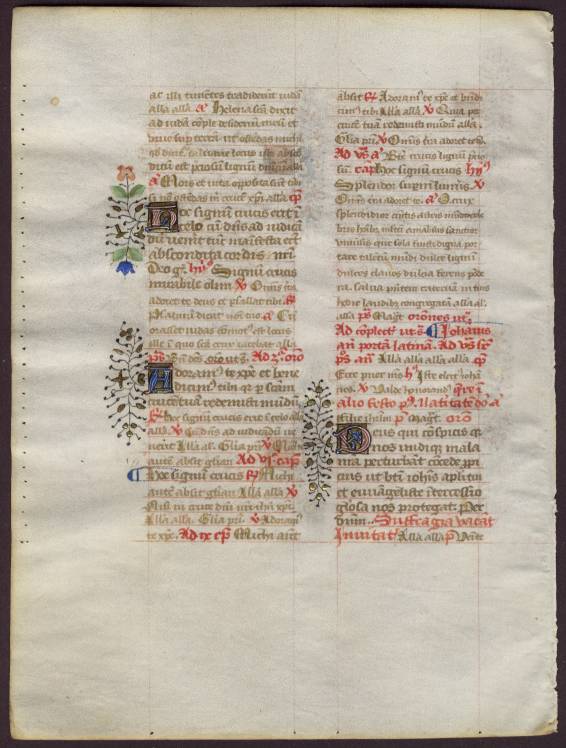

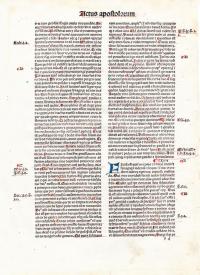

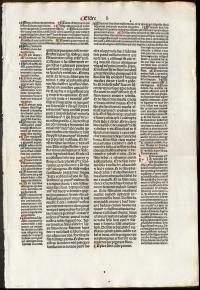

Incunabula Leaf, 1483 Latin Vulgate, Acts 13:7 -15:36. Printed by Johannes Herbort de Seligenstadt, Venice. 237 x 192 mm, 8.0" x 11.0" ($50.00)

Incunabula Leaf, 1483 Latin Vulgate, Acts 13:7 -15:36. Printed by Johannes Herbort de Seligenstadt, Venice. 237 x 192 mm, 8.0" x 11.0" ($50.00)During the Renaissance (14th to 17th century), increasing knowledge of ancient languages and culture were applied to the study of Christianity. “Back to the sources” was the watchword of the humanists as they searched for the true meaning of the Bible. The Italian Lorenzo Valla was the first of the humanists to attempt a correction of the Vulgate’s Latin based on the Greek original. This leaf is from a Fontiubus ex Graecis edition, “a series of corrected Latin Bibles, which claim for themselves—apparently with justice—a superiority above all contemporary editions,” according to Darlow and Moule, vol. II, p. 911. This edition had numerous additions by Franciscus Moneliensis and Quintius Aemilianus.

When one hears about a textual variant in the Bible, the reaction should not be “I’ve never heard of that before!” or “That’s not in my King James Version of the Bible!” but rather the response should be, “What was originally written by the author?” The earliest and best texts state that Luke, in the Acts of the Apostles 15:33, wrote “And after they had stayed there awhile, they were let go in peace from the brethren to those who had sent them.” This is strongly supported by the seventh-century Papyrus #74, the Greek Codex Sinaiticus, the Greek Codex Alexandrinus, the Greek Codex Vaticanus, the Greek Codex Ephraimi Rescriptus, the Greek Codex Bezae, the Sahidic Coptic, the Bohairic Coptic, and the Latin Vulgate (as seen here, with the wording “ad eos q miferat illos” or “ad eos qui miserant illos,” meaning “to those who had sent them.” Instead of “to those who had sent them,” later readings have “to the apostles.” According to Bruce M. Metzger in A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, p. 439, the later reading “appears to be a deliberate alteration introduced by copyists in order to bring the apostolate into greater prominence.” In the Wyclif Bible (1380-95), this phrase is translated as “to them who had sent them,” as it is in Coverdale’s Latin/English Diglot (1538). However, English translations from Tyndale (1525) until the 20th Century use “to the apostles” even though it does not represent the original text as written by Luke. Most Bibles from the 1970s on return to the original translation, “to those who had sent them.”

Folio size, two columns, 58 lines, black letter (Gothic script) type. Leaf has rubrication in blue ink, red ink, and yellow ink; there are scores of marks, underlinings, and flourishes on this leaf. It has two large handwritten initial letters: one in blue ink and one in red ink.

This was printed just 28 years after Gutenberg’s first Bible of 1455. By definition, an incunabulum (the singular of “incunabula”) must be printed from 1455 to 1500. In Latin, the term “incunabula” means “baby clothes” or “things of the cradle,” and can refer to the earliest stages or first traces in the development of anything. Books printed in the later 1480s and the 1490s, as well as the year 1500 (which is technically the last year of the 15th century), had more woodcut printed initials than earlier ones.

We need to put into context the work of Christian scribes during the last 2,000 years. During these centuries scribes developed two kinds of abbreviations in the manuscripts that were copied and re-copied. The first kind of abbreviation was the shortening or abbreviation of very common words, so that it was easier and quicker to write them. These do not concern us here. The second kind of abbreviation was for the words held sacred by Christians. In the Latin tradition, and especially in the Latin Vulgate text, these were called “Nomina Sacra” meaning “Holy Names.” The common examples of Nomina Sacra are Lord, God, Jesus, Christ, Holy Spirit, the Father, and the Son. This leaf has the Nomina Sacra or Holy Name for the word “JAHWEH” or the “LORD” as it is given in the King James Version. It appears in the abbreviated form “dns” or “dni” (with a long line above the “n” to indicate it is a sacred abbreviation showing respect for the name). There are eight instances this sacred abbreviation, as well as one instance of the nomina sacra for Christ. [Ref: Bibliographic description in Frederick R. Goff, “Incunabula in American Libraries,” as #B-579]

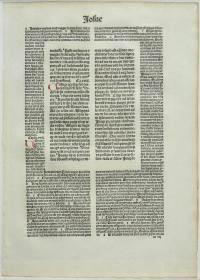

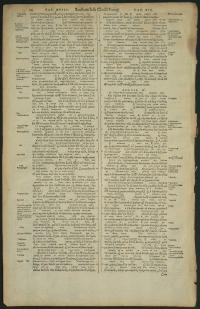

Incunabula Leaf, 1487 Latin Vulgate, Joshua 17:17 - 19:11. Printed by Anton Koberger, Nuremberg, Germany, 8.5" x 12.1" ($22.00)

Incunabula Leaf, 1487 Latin Vulgate, Joshua 17:17 - 19:11. Printed by Anton Koberger, Nuremberg, Germany, 8.5" x 12.1" ($22.00)One of the many printings of a continually corrected Vulgate. The printer, Anton Koberger (c. 1445-1513), established the first printing house in Nuremberg in 1470. An ambitious businessman, he quickly became the most successful publisher in Germany, and at his peak, had 24 presses in operation and employed 100 craftsmen. His workshops produced about 200 works before 1500. He prized beautiful texts and promoted the inclusion of decoration in printed works. He and his godson, Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), actively collaborated on the development of woodcut illustrations. Koberger closed the Nuremberg printing house in 1504.

Printed in black letter, double columns, 30 lines of 14-pt scripture in center block surrounded by 72 lines (10-pt) of extensive commentary. Red initial capitals by hand and capitals throughout the text touched in red.

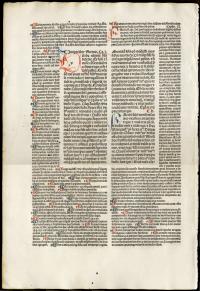

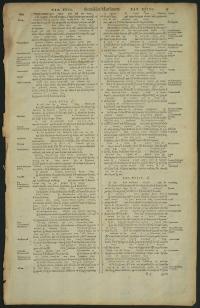

Incunable leaf, 1489 Biblica Latina Cum Postillis,, Latin, Ezra 10:4 - Nehemiah 2:5. Printed by Octavianus Scotus, Venice. 293 x 189 mm, 9.8" x 14.2" ($100.00)

Incunable leaf, 1489 Biblica Latina Cum Postillis,, Latin, Ezra 10:4 - Nehemiah 2:5. Printed by Octavianus Scotus, Venice. 293 x 189 mm, 9.8" x 14.2" ($100.00)The extensive commentary of this Latin Bible was written by the Franciscan theologian Nicholas de Lyra (1270-1340). He was a scholar familiar with Hebrew and stressed the need to go to original sources for interpreting the Bible rather than rely on what he called corrupted Latin translations. His commentary was printed for the first time in 1471-72 which makes it the first printed commentary of the entire Bible.

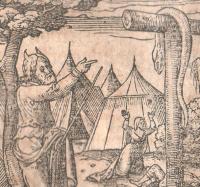

One of the first Venetian books to make extensive use of woodcuts, this Bible with surrounding commentaries includes forty-seven illustrations and diagrams. The designs for the woodcuts in this edition have been attributed to the “Master of the Pico Pliny,” the anonymous but prolific artisan who previously had specialized in the illumination of Venetian manuscripts and printed books.

Folio size heavy paper leaf from a 4-volume set. Scripture is 54 lines (31 lines on reverse) of 14-point type surrounded by 77 lines of 11-pt commentary, both in double columns. Three-line initials in red and blue by hand in both scripture and commentary. Also alternating red and blue paragraph symbols in the commentary. Has 8 small wormholes. [Goff B-616; BMC V, 437]

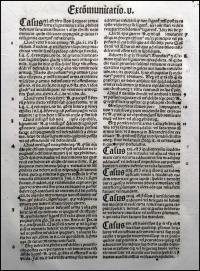

Incunable Leaf, c.1490 Summa angelica de casibus conscientiae,, Latin (The main angelic cases of conscience). Printed by Anton Koberger, Nuremberg. 215 x 146, 7.1" x 9.8" ($13.51)

Incunable Leaf, c.1490 Summa angelica de casibus conscientiae,, Latin (The main angelic cases of conscience). Printed by Anton Koberger, Nuremberg. 215 x 146, 7.1" x 9.8" ($13.51)Angelo Carletti di Chivasso (1411-1495) received two doctorate degrees from the University of Bologna and later entered the Franciscan Order. His best known work is the Summa angelica de casibus conscientiae. The Summa is a reference work divided into 659 entries in alphabetical order, forming what might be best termed a dictionary of moral theology. This particular page focuses on the causes of excommunication. The first edition of the Summa angelica appeared in 1476, and by 1520 had gone through 31 editions. The work was condemned by protestant reformers, and Martin Luther publicly burned a folio-size fifth edition of it, probably chosen for theatrical appeal.

This work belongs to the genre known as “cases of conscience” and the field of casuistry. Following the Council of Trent (1545-1563), theologians systematically addressed questions regarding personal, social, political, and religious duties, specifically in terms of the relative rights of Church and State. The order of authority was first biblical (divine) law, next natural law (which tended to be poorly defined), and finally canon law (law of man). Casuistry (from Latin casus) is now used in juridical and ethical discussions of law and ethics. It is the origin of case law in common law, and the standard form of reasoning applied in common law.

The printer, Anton Koberger, prized beautiful texts and promoted the inclusion of decoration in printed works. This Summa is octavo size, printed in a modified black letter typeface, double columns, 58 lines, paragraph numbers in the margins.

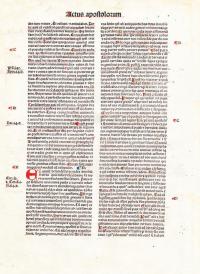

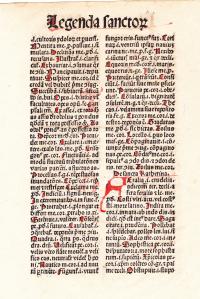

Incunabula Leaf, 1494 Medieval Latin Mammotrectus. Printed by Martin Flach, Strassbourg. 146 x 82, 5.5" x 8.0" ($30.00)

Incunabula Leaf, 1494 Medieval Latin Mammotrectus. Printed by Martin Flach, Strassbourg. 146 x 82, 5.5" x 8.0" ($30.00)Johannes Marchesinus (or Giovanni Marchesini) was an Italian Franciscan friar or monk from Marchesio in the province of Reggio Emilia, near Modena. He taught in Imola, Faventia and Bologna and is the author of many homiletic and educational works. This leaf, written around 1300, is from his most famous work, the Mammotrectus super Bibliam, which means “The Breast-Feeding Milk about the Bible” or “The Nourisher on the Bible,” i.e., the Basics. The Mammotrectus is an early guide to understanding the text of the Bible and was very popular with preachers in the later Middle Ages. It explained difficult words in the Scriptures, both etymologically and grammatically, and provided explanations of the festivals of the Church year, the legends of the saints, and various liturgical texts. It was especially used within the Franciscan order for semantic and liturgical instruction of the novices.

The heading of the page on the left side reads, “Legenda Sanctorum,” which means “The Legends of the Saints.” The heading on the right page, “Fo[lium] CCLII,” which means “Folio #252" (page 252). Other words on this leaf are: “Saint Katherine, The Blessed Clement, St. Crisagano” (Chrysoganus), “Divine, Great, Participation, Resplendent, Interjection, Nutriment, Spectator, Gladiator, Bible, Blood, Figure, Image, Form, Death, Sacrilege, Burden, Sign, Dignity, Latin, Prudent, Sophistication,” and “Wisdom.”

Printed just 39 years after Gutenberg’s work of 1455. By definition, an incunabulum (the singular of “incunabula”) must be printed from 1455 to 1500.

Printed in black letter type, double columns, 37 lines per column, three initial capitals by hand in red, also red rubrication marks to highlight letters and underline some of the text. [Ref: Full bibliographic description is found in Frederick R. Goff, “Incunabula in American Libraries,” M-253; also see Hain II,1, M10573; BMC I, 150]

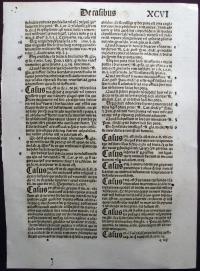

Incunable leaf, 1497 Biblica Latina Cum Postillis, Latin, 2 Kings 21-22. Printed by Anton Koberger, Nuremberg. 279 x 204, 9.1" x 13.3" ($29.00)

Incunable leaf, 1497 Biblica Latina Cum Postillis, Latin, 2 Kings 21-22. Printed by Anton Koberger, Nuremberg. 279 x 204, 9.1" x 13.3" ($29.00)The extensive commentary of this Latin Bible was written by the Franciscan theologian Nicholas de Lyra (1270-1340). He was a scholar familiar with Hebrew and stressed the need to go to original sources for books of the Bible rather than rely on corrupted Latin versions translated later. This leaf comes from the first volume of a four-volume set (Genesis through Chronicles). It contained the usual introduction from St. Jerome but perhaps the most interesting aspect of Volume 1 was that pages 169 - 184 (Leviticus 23 to Numbers 22) were omitted because they had been misplaced at the time of binding.

Folio size heavy paper. Bible text is 28 lines (30 lines on reverse) of 13-point black letter type surrounded by 72 lines of 11-pt commentary, both in double columns. Red initial capital L by hand opens the chapter. [Hain 3171, Proctor 2115, Goff B-619]

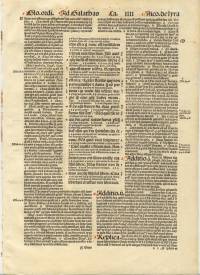

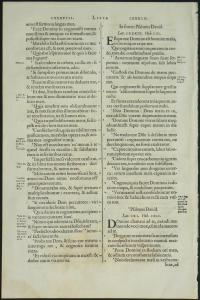

Incunable leaf, 1498 Biblica, Latin, Galatians 4:25 - 5:11. Printed by J. Froben and J. Petry, Basel. 252 x 186 mm, 8.1" x 11.5" ($23.00)

Incunable leaf, 1498 Biblica, Latin, Galatians 4:25 - 5:11. Printed by J. Froben and J. Petry, Basel. 252 x 186 mm, 8.1" x 11.5" ($23.00)The extensive commentary of this Latin Bible was written by the Franciscan theologian Nicholas de Lyra (1270-1340). Letter notations on both sides of scripture text were used prior to verse numbers and were referenced by Eusebius in his Canon tables of the four Gospels.

Octavo size heavy watermarked paper. Bible text is 14-point black letter interspersed with 8-pt references. Surrounding commentary is 72 lines of 9-pt type. Initial capitals in red and blue with red rubication throughout. [Goff B-609, Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke, 4284]

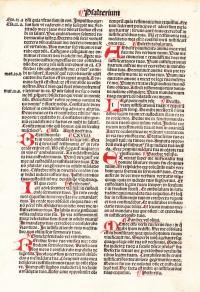

Incunabula leaf, 1500 Latin Vulgate, Psalms 117-118, Printed by Anton Koberger, Nuremberg. 247 x 170, 8.5" x 11.0" ($100.00)

Incunabula leaf, 1500 Latin Vulgate, Psalms 117-118, Printed by Anton Koberger, Nuremberg. 247 x 170, 8.5" x 11.0" ($100.00)One of the many printings of a corrected Vulgate. Text contains Psalms, Chapters 117-118, which in later translations is Ch 118-119. It was printed before verses were numbered, so each chapter has only alphabetic “sections” listed in the margin as A, B, C, D, etc. Also, there is a Chapter Summary (listed as C.S.) of its contents before the beginning of each chapter. This leaf is very interesting for having Psalm 119, which in Hebrew has lines that begin with each of the Hebrew letters in order. This is not seen, of course, in the Latin translation or any English translation, but is clear in the Hebrew. Notice also after the name of the Hebrew letter, there is a Latin translation of its meaning in Hebrew: for example, Beth = domus = house, Gimel = retributio = retribution, Heth = vita = live, Teth = bonum = good, and Ayin = oculus = eye.

Printed in black letter, double columns, 58 lines per column, minimal scripture references on left side only. Initial capitals in red by hand, also red rubrication marks to highlight letters and paragraphs.

This leaf has the Nomina Sacra or Holy Name for the word “JAHWEH” or “LORD.” It appears 22 times in the abbreviated form “dns” or “dne” (with a long line above the “n” to indicate it is a sacred abbreviation). These contractions actually show respect for the names. Interestingly, those words are not highlighted in red.

Original leaf, 1506 Biblij Cžeská, w Benátkach tisstená [Czech Bible printed in Venice], Psalms 9:1 - 16:2. Printed by Petrus de Lichtenstein, Venice, Italy. 274 x 207, 8.8" x 12.3" ($33.20)

Original leaf, 1506 Biblij Cžeská, w Benátkach tisstená [Czech Bible printed in Venice], Psalms 9:1 - 16:2. Printed by Petrus de Lichtenstein, Venice, Italy. 274 x 207, 8.8" x 12.3" ($33.20)A medieval translation of the Bible into Czech, revised according to the Vulgate, by the Bohemian religious reformer Jan Hus, who was burned at the stake as a Roman Catholic heretic in 1415. The revision was continued by others during the 1400s and first printed at Prague in 1488, which edition is now extremely rare. This leaf is from the third edition of 1506, further edited by Jan Gindrzysky of Saaz and Thomas Molek of Hradec and financed by three wealthy citizens of Prague.

The Republic of Venice provided safe haven for many refugee European printers such as this printer of the old and influential Lichenstein family of Cologne. At this time jurisdiction over Bohemia (modern Czech Republic) was hotly contested between Poland and Hungary.

Translating the name of this Bible, at least one scholar concluded that “Benátkach” meant Bohemian, and others blindly followed. In fact, the word is the Bohemian name of Venice! “Tisstená” loosely means “printed” and “w” means “in,” viz “in Venice printed.”

This is a very early example of Bohemian printing, done in an especially charming antique Gothic typeface reminiscent of the earliest Germanic printing, double columns of Bohemian language text, 52 lines, minimal sidenotes. Extensively rubricated with 7 hand painted Uncial initial letters, with text emphases in red and blue inks. Note that the printer has printed each of the seven letters in black to be later drawn in by hand in color. [Ref: Darlow & Moule 435 and Sketch of the History of the Bible Bohemia by G. W. Malin]

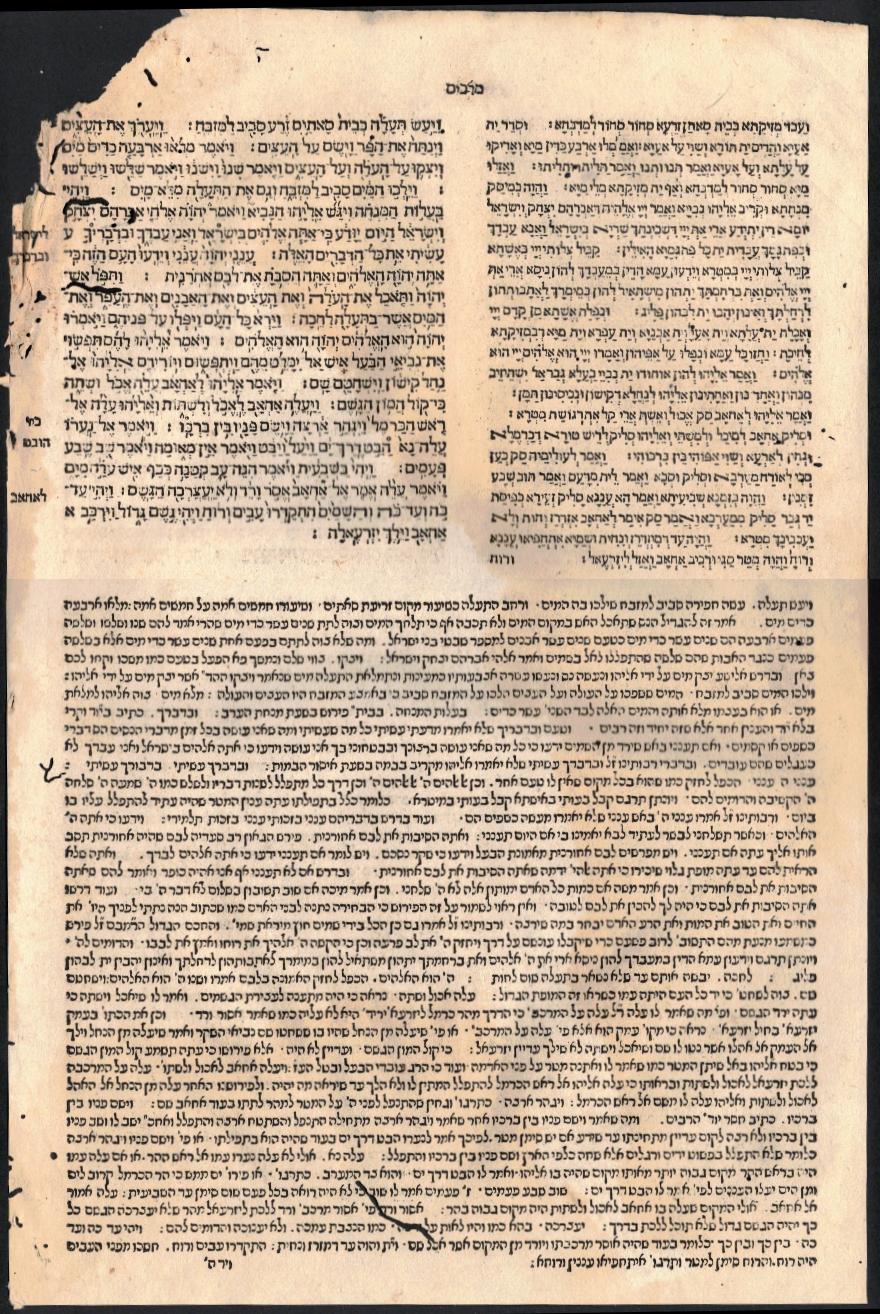

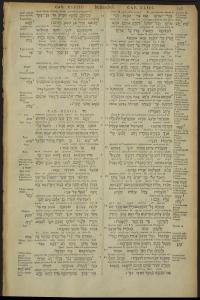

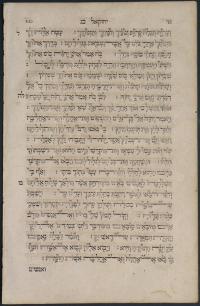

Leaf, 1517 Mikra'ot Gedolot [Rabbinic Bible], 1 Kings. Printed by Daniel Bomberg, Venice, Italy. 285 x 190 mm, 8.5" x 13.0" ($62.00)

Leaf, 1517 Mikra'ot Gedolot [Rabbinic Bible], 1 Kings. Printed by Daniel Bomberg, Venice, Italy. 285 x 190 mm, 8.5" x 13.0" ($62.00)In 1516 Daniel Bomberg, a wealthy Christian from Antwerp, was granted permission to publish Hebrew books in Venice. Among the first works he printed was the Mikra'ot Gedolot (Rabbinic Bible), a folio edition of the entire Bible with leading commentaries. Pope Leo X gave his imprimatur for this book and Felix Pratensis, a monk who had been born a Jew, was the editor. Commentary was by Rabbi David Kimhi (Rada’k).

Bomberg published the edition because of growing interest in the Hebrew language and the Bible among learned Christians. An adept businessman, Bomberg quickly perceived that there was also a substantial market for Hebrew texts among the Jews of Italy, whose numbers had been increased by an influx of Spanish and Portuguese Jews exiled from the Iberian Peninsula. Many Jewish readers were attracted to this Bible, but conversely, being edited by an apostate, a few translation errors, and the blessing of the Pope led many Jews to avoid this first edition.

Scripture printed in Hebrew (14 point) and Aramaic (12 point) in two columns with commentary below in one wide column of 12-point type. Page torn upper right and worm damage top right and bottom.

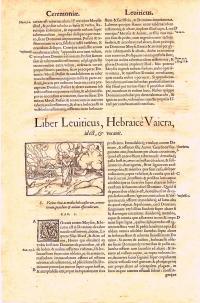

Replica Leaf, 1517 Complutensian Polyglot Bible, Leviticus 11:36 - 12:8. Original printed by Alcala de Henares, Spain. Reprint by Art.com, 14" x 20" image size on 18" x 24" sheet. ($22.48)

Replica Leaf, 1517 Complutensian Polyglot Bible, Leviticus 11:36 - 12:8. Original printed by Alcala de Henares, Spain. Reprint by Art.com, 14" x 20" image size on 18" x 24" sheet. ($22.48)The earliest polyglot Bible, the Complutensian, was compiled by a team of scholars led by the archbishop of Toledo (Spain), Francisco Jimenez de Cisneros, between 1514 and 1517, although the completed 6-volume work had to wait for approval by the pope and was not published in its entirety until 1522. The Old Testament includes the Hebrew Masoretic text, the Latin Vulgate, the Greek Septuagint, and an Aramaic paraphrase (Targum Onkelos) of the Pentateuch,. The Hebrew, Vulgate, and Greek are in three columns and below them is the Aramaic paraphrase and its Latin translation. About 600 Complutensian Polyglot Bibles were printed and only about 120 exist today in their complete form.

Both religious traditionalists and the Catholic Church feared that Bible study by laymen might lead to heresy; also growing anti-Semitism in Spain promoted a fear of the Hebrew language so several scholars who contributed to the Complutensian were persecuted by the Inquisition.

Replica Leaf, 1516-22 Novum Instrumentum omne [New Testament], Greek and Latin, by Desiderius Erasmus, Revelation 22:8-21 (last page). Printed by Johann Froben, Basel.

Replica Leaf, 1516-22 Novum Instrumentum omne [New Testament], Greek and Latin, by Desiderius Erasmus, Revelation 22:8-21 (last page). Printed by Johann Froben, Basel.Although the first printed Greek New Testament was the Complutensian Polyglot (1514), this was the second to be published, in five editions from 1516 to 1535. For his translation, Erasmus used several Greek manuscripts housed in Basel, but some passages he translated from the Latin Vulgate.

Of the five editions of Novum Instrumentum omne, four and five are not regarded as being so important as the third edition (1522), which was used by Tyndale for the first English New Testament (1526), Luther, and later by translators of the Geneva Bible and the King James Version. The third edition included the Comma Johanneum (a short added clause in 1 John 5:7-8 considered a Latin corruption by most scholars). The Erasmian edition was the basis for the majority of modern translations of New Testament in the 16-19th centuries.

Printed in Greek and Roman type, two columns (Greek on left, Latin on right), 40 lines.

Leaf, 1519 Biblia Latina, 2 Corinthians 9-12. Printed by Jacques Mareschal, Lyon. 143 x 109, 4.9" x 6.7" ($15.00)

Leaf, 1519 Biblia Latina, 2 Corinthians 9-12. Printed by Jacques Mareschal, Lyon. 143 x 109, 4.9" x 6.7" ($15.00)From an early printing of a Biblia Latina, “Biblia cum summarioru(m) apparatu pleno qaudrupliciq(ue) repertorio insignita.” Printed by Jacques Mareschal for Simon Vincent.

During the 16th Century, Lyon was the most important center for printing in France. Jacques (alias Roland) Mareschal (1475-1529) was a master printer, a “seller” by 1522, as well as a “courier” for the Co-Fraternity of the Printers, a powerful guild organization of the age. Aside from this St. Jerome Bible, Mareschal was well known for his much-copied 1512 edition of the Bible as well as later versions in 1523, 1525 and 1526. Simon Vincent, one of three major publishers in Lyon at the time (along with Gueynard and Jacques Guinta), contracted with several printers simultaneously, Mareschal being one of them. Variations on the colophon might include the publisher’s name or mark only, or both publisher and printer’s name. Simon Vincent also published such famous works as Luis Coronel’s “Physicae Perscrutationes” (1512), Coronel being a personal friend and supporter of Erasmus.

Printed in small 8-pt black letter, double columns, 56 lines per column, with four 8-line historiated letters at the beginning of each chapter. Tiny 6-pt sidenotes and scripture references. [Ref: Adam’s B 997; Baudrier XI, 401; Bibelslg. D WLB Stgt. D 276; Tanks VII, 324, 399; Lyon, France, 2008; Pogue, 1987, 42; UF Library, 2008; Stock, 1882, 86; Davis, 1966, 54; Bietenholz and Deutscher, 1987, 343].

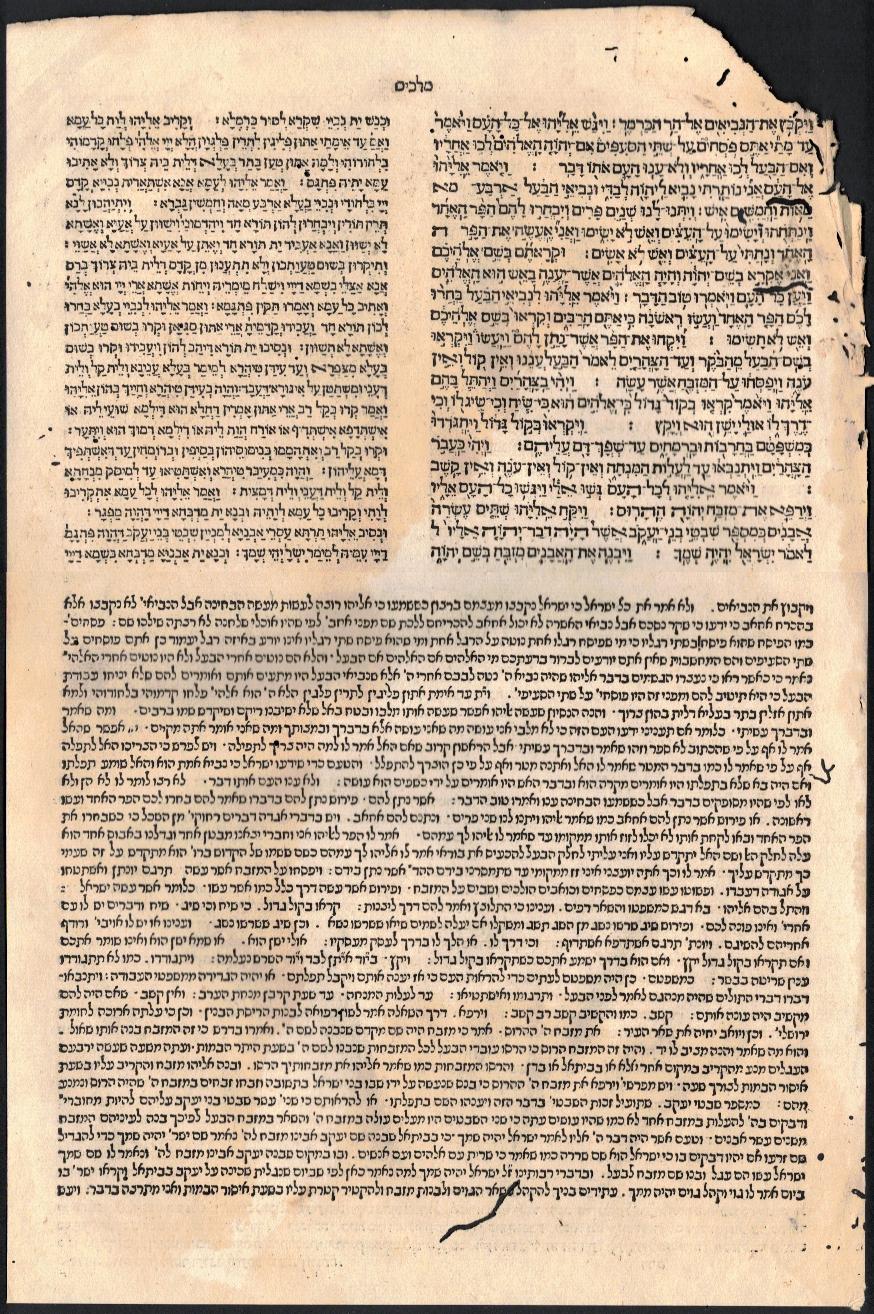

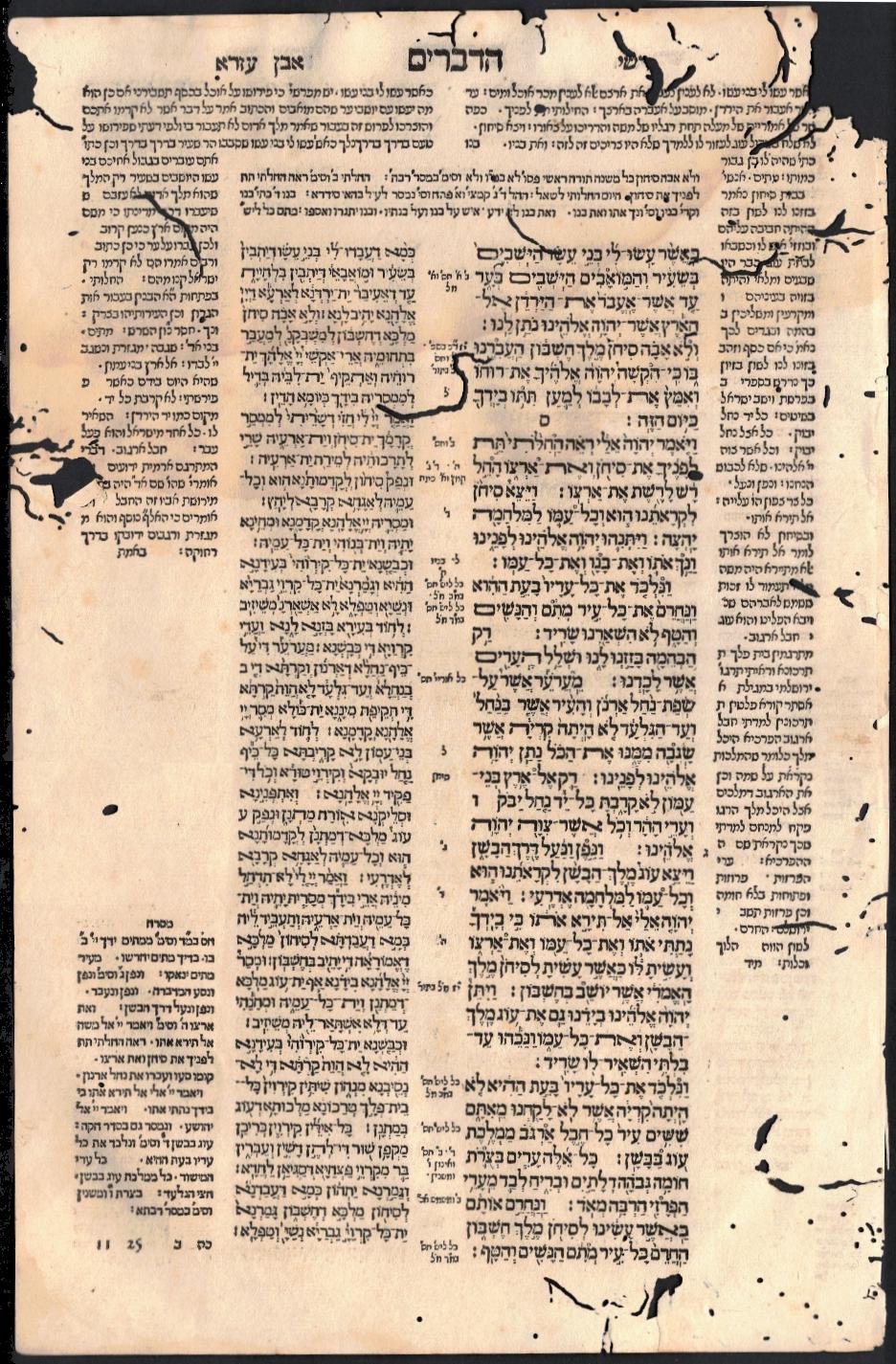

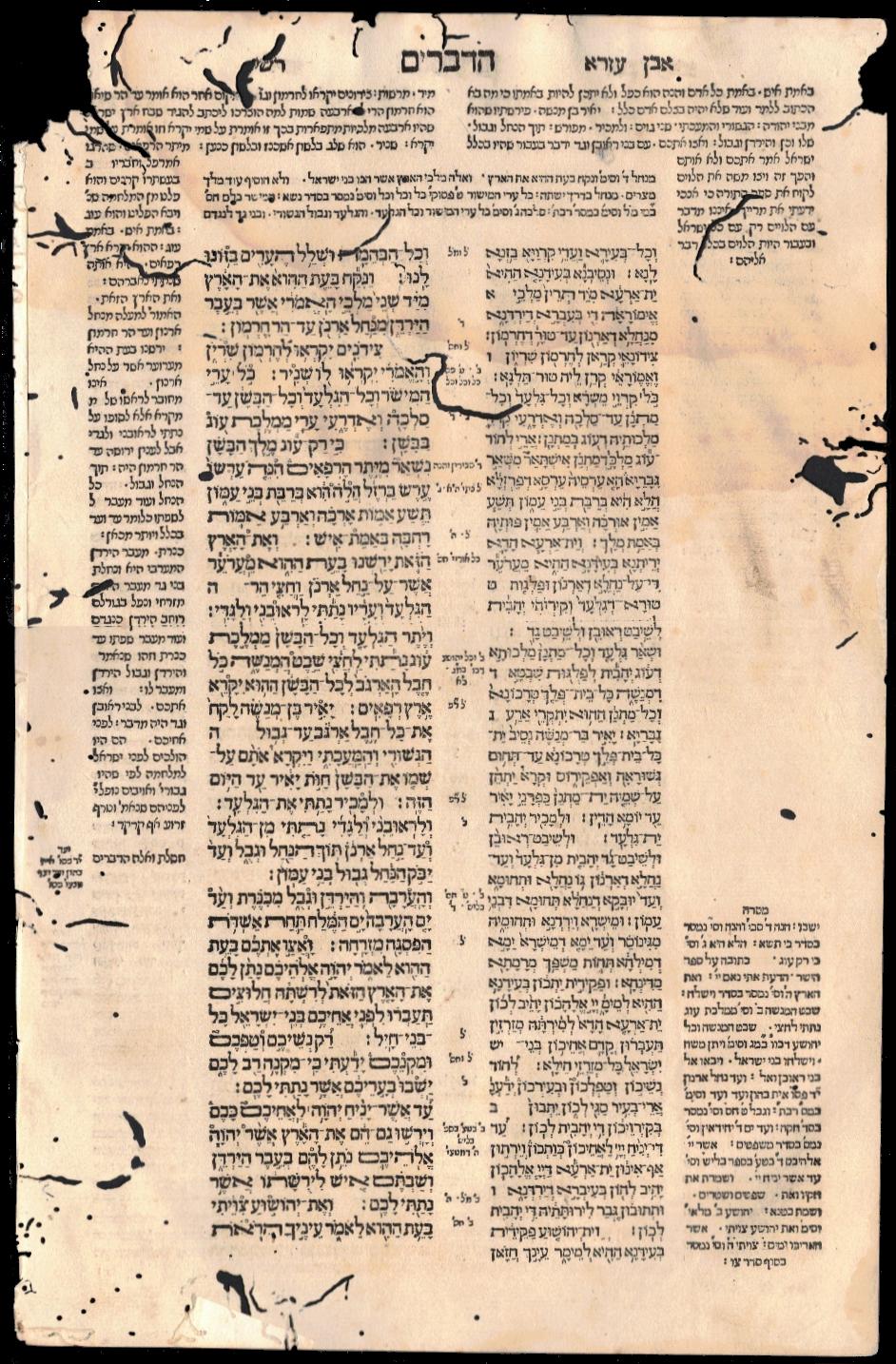

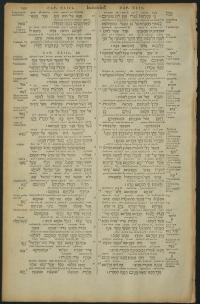

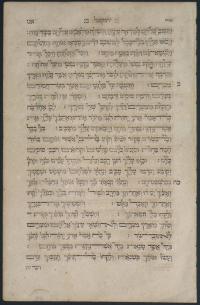

Leaf, 1524 Sha’ar HaShem ha-Hadash [Second Rabbinic Bible], Deuteronomy 1. Printed by Daniel Bomberg, Venice, Italy. 320 x 210 mm, 9.0" x 14.0" ($48.90)

Leaf, 1524 Sha’ar HaShem ha-Hadash [Second Rabbinic Bible], Deuteronomy 1. Printed by Daniel Bomberg, Venice, Italy. 320 x 210 mm, 9.0" x 14.0" ($48.90)Among the first works printed by Daniel Bomberg in 1516–17 was the Mikra'ot Gedolot (Rabbinic Bible), a folio edition of the entire Bible. The Bible attracted Jewish readers, but the editorship of Felix Pratensis, an apostate, a few translation errors, and the blessing of the Pope led many Jews to avoid the 1516-17 edition.

Six years later, in 1524, Bomberg's second Rabbinic Bible appeared, the first to include the Masorah. No effort was spared to produce the finest Bible possible. It was printed in four volumes, each with its own title-page. The initial word of each book is set within a large decorative woodcut frame surrounded by a square made up of lines, varying in number, comprising the Masoretic rubrics. At the end of each book is the Masoretic summary. Each page is arranged in four columns, with the inner columns comprising the Hebrew Biblical text and the Aramaic translation, Targum Onkelos. The outer columns contain the commentaries of Rashi and ibn Ezra. Above and below the inner columns is the Masorah Magna and in the space between these two columns is the Masorah Parva. In the narrow outer column are portions of the Masorah Parva that did not fit between the text and Targum.

This time Bomberg emphasized that his printers were pious Jews, as was his scholarly editor, Jacob ben Haim ibn Adonijah. The second Rabbinic Bible became the determinative Biblical text, first for Jews and subsequently for the scholarly world as well. All future editions reflected this outstanding edition. Bomberg's press was active until 1549 and in all, more than two hundred Hebrew books were produced in his shop.

Scripture printed in Hebrew (large 18 point type) and Aramaic (14 point) in two columns with commentaries at top and side in 11-point type. Page torn upper left and right with serious worm damage overall.

Leaf, 1526 Biblia Graeca, Greek, Ezra 8-9, page 216. Printed by Wolfe Kopfel, Strasbourg. 122 x 66, 3.9" x 6.4" ($12.50)

Leaf, 1526 Biblia Graeca, Greek, Ezra 8-9, page 216. Printed by Wolfe Kopfel, Strasbourg. 122 x 66, 3.9" x 6.4" ($12.50)This leaf is from the third edition of the complete Greek Bible edited by Luther’s friend and disciple Johannes Lonicerus (Lonitzer). It is from Volume 2 of a 4-volume set that includes the Apocrypha with the four parts of Maccabees, the fourth supposedly written by Jospehus. The Old Testament follows the Aldine Bible (Septuagint) of 1518 rather than the Complutensian. The New Testament first appeared in 1524 and was re-issued in 1526 to form Volume 4 of this complete Bible.

Octavo leaf has 30 lines of Greek type printed on laid paper, single column with 4-line indent and guide letter for later addition of a woodcut initial K. Two 1-line indents are also left for a design or initial in two paragraph openings. [Adams B-977; Darlow & Moule 4602]

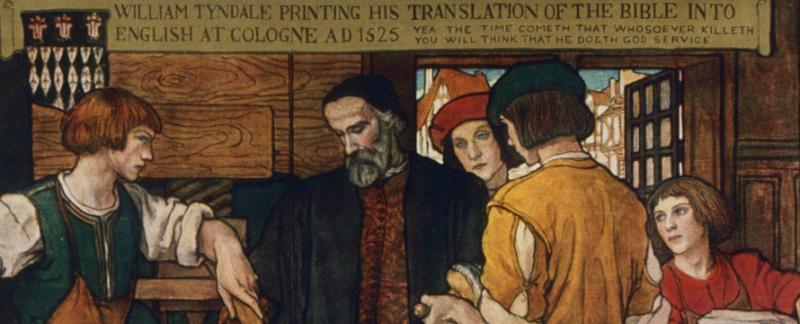

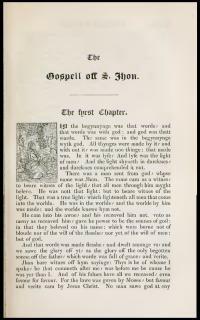

Reprint Bible, 1526 Tyndale New Testament. Reprinted verbatim by Stevens and Pardon for Samuel Bagster, London, 1836. 720 pages. 5.0" x 7.6" ($478.61)

Reprint Bible, 1526 Tyndale New Testament. Reprinted verbatim by Stevens and Pardon for Samuel Bagster, London, 1836. 720 pages. 5.0" x 7.6" ($478.61)Paraphrased from the preface: “To the martyred William Tyndale are we indebted for the first translation of the New Testament into the English vernacular tongue. His life forms an important era in religious history and as long as the English tongue is spoken his memory will be imperishable.”

Born around 1494, Tyndale studied at Oxford and Cambridge, eventually taking holy orders. Deeply convicted that Scripture should be available to everyone, he sought permission to translate the Bible from Bishop Cuthbert Turnstall in London. When the request was denied, Tyndale left England for Europe. Subsidized by a layman friend, Humphrey Monmouth, by August of 1525, Tyndale and his assistant, William Rowe, had translated Erasmus’ Greek New Testament into English. After Tyndale was forced to flee from Cologne, it was published by Peter Schoeffer in Worms in smaller octavo format. By October 1526 copies were being smuggled into England, where, unfortunately, many of them were burned. Only three copies survive. Revised editions were published in 1534 and 1535.

By 1529, Tyndale had mastered enough Hebrew to produce outstanding translations of the Pentateuch and nine other Old Testament books. These were later published in the Matthew Bible edited by John Rogers.

In 1535, Henry Philips lured Tyndale from safety in Antwerp, Belgium to Vilvoord (near Brussels) where he was arrested, imprisoned for nearly two years, tried for heresy, condemned, and on October 6, 1536 strangled and burned at the stake. Tyndale’s dying words were, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.”

This is an exact copy, rebound, of the Tyndale New Testament of 1526 except that a Roman typeface has been employed to make it more readable and useful. Smallish 8-pt type in a single column of 43 lines. Includes a 98-page Memoir of William Tyndale by George Offor plus a list of revisions between Tyndale’s first 1525-26 translation and his later translation of 1534. With engraved portrait of Tyndale as frontspiece. Copies of this reprint in good condition are very scarce. [Herbert 1816]

Facsimile Bible, 1537 Matthews Bible, Published by Hendrickson Publishers, 2009. Hardback, 1080 pages, 7.0" x 10.0" ($23.00)

Facsimile Bible, 1537 Matthews Bible, Published by Hendrickson Publishers, 2009. Hardback, 1080 pages, 7.0" x 10.0" ($23.00)The Matthews Bible brings together the work of two giants of 16th century English Bible translation. William Tyndale and Myles Coverdale shared a vision of making the scriptures available to ordinary believers concerned that their authority might be undermined in a time when kings and clerics alike opposed translating them into English. John Rogers combined Tyndale’s and Coverdale’s texts—supplying some translation work of his own—to create the Matthews bible. It was attributed to a fictitious “Thomas Matthew,” concealing the inclusion of Tyndale’s text so King Henry VIII would license production of the volume. So popular became the Matthews Bible that bishops were encouraged to order copies for their parishes.

For his efforts, John Rogers was sentenced to death by Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of London, for heretically “denying the Christian character of the Church of Rome and the real presence in the sacrament.” He was burned at the stake on 4 February 1555 followed a year later by his supporter and patron, Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, on 21 March 1556.

This is a facsimile of one of the finest existing copies of the Bible with a new introduction by Dr. Joseph W. Johnson, a lifetime member of the Tyndale Society.

Facsimile Bible, 1538 Latin/English Diglot New Testament. Published by Bible Reader’s Museum, 2007. 575 pages, 8.3" x 10.7" (49.00)

Facsimile Bible, 1538 Latin/English Diglot New Testament. Published by Bible Reader’s Museum, 2007. 575 pages, 8.3" x 10.7" (49.00)Title page reads, “The new testament both in Latin and English after the vulgare texte which is red in the churche. Translated by Myles Coverdale, and prynted in Paris by Fraunces Regnault 1538 in Novembre. Prynted for Richard Grafton and Edward Whitchurch, citizens of London.”

Between 1529 and 1535, Myles Coverdale worked with Tyndale on translations of the old testament in Hamburg and Antwerp. Coverdale published the first edition of his Bible in October 1535 and although it won King Henry VIII’s verbal approval, it was not accepted as authoritative because its prologue and notes reflected Luther’s reforms and it was felt the translation was too far from the original texts.

This third corrected edition of Coverdale’s diglot has a narrow 1.8" column with the Latin text in 12-point Roman type and a wider 3.2" column with the English in a large 15-point black letter type (49 lines), plus a third narrow column of references in Roman type. [Original: Herbert 39 and STC #2817]

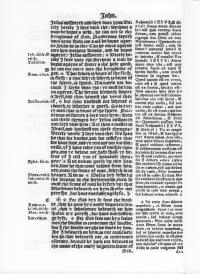

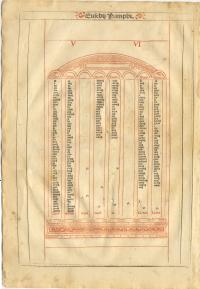

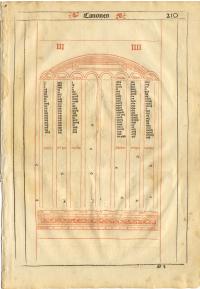

Leaf, 1539 Biblia Latina, Canon Tables 3 to 6. Printed by Joannis Crispini, Lyon. 300 x 206, 9.5" x 13.4" ($22.00)

Leaf, 1539 Biblia Latina, Canon Tables 3 to 6. Printed by Joannis Crispini, Lyon. 300 x 206, 9.5" x 13.4" ($22.00)This Bible is a close copy of Jacques and Jean Mareschal’s Lyon Bibles of 1525. It is also closely related to Jacob Sacon’s Bibles. Crispini, originally of the French/ Netherlands province of Artois, printed for a time in Lyon before fleeing religious persecution and opening a press in Geneva in 1548. He died of the plague in 1572.

In the Canon tables, Eusebius classified the sections of the Gospels to show at a glance where each one agreed with or differed from the others. Face of leaf contains the Eusebius Canon Table III (Matthew, Luke, John) and IV (Matthew, Mark, John) in red and black. Verso contains Canon Table V (Matthew, Luke) and VI (Matthew, Mark). The sections as cited here are indicated in the margin of nearly all Greek and Latin manuscripts of the Bible, but do not correspond to chapters and verses in later Bibles from 1553 on.

Canon tables are often quite elaborately decorated and illustrated. This one is not and has a simple red arch with 8 column divisions. Type is 8-point black letter. [Fairfax Murray 36, Not in Darlow & Moule]

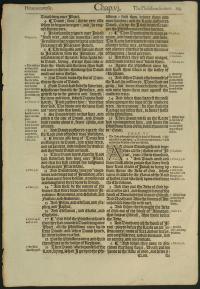

Leaf, 1549 edition of 1537 Matthew Bible, English, Exodus 26:9 - 28:27 with small woodcut of Aaron as priest. Printed by John Daye and William Seres, London. 257 x 164, 7.8" x 11.4" ($88.00)

Leaf, 1549 edition of 1537 Matthew Bible, English, Exodus 26:9 - 28:27 with small woodcut of Aaron as priest. Printed by John Daye and William Seres, London. 257 x 164, 7.8" x 11.4" ($88.00)The Matthew Bible was the second version of the Bible in Early Modern English, edited by John Rogers, who wrote under the pseudonym of Thomas Matthew, either in fear of his life or to conceal the fact that a considerable part of this Bible was from the condemned translation of Tyndale (with revisions from Coverdale). Unfortunately, in 1555, John “Thomas Matthew” Rogers and Thomas Cranmer were both burned at the stake under Queen “Bloody” Mary.

The 1549 edition is also known as the “Becke Bible,” resulting from the dedication by Edmund Becke; also called the “Indecent Bible,” because of many objectionable notes; and the “Wife-Beater’s Bible,” from a note on 1 Peter 3:7, “And yf she be not obedient and healpefull unto hym, endevoureth to beate the feare of God into her heade, that therby she maye be compelled to learne her duitie and do it.”

Printed in rather peculiar 10-pt black letter, double columns, with 65 lines per column. References and a few notes in the margins in black letter. Has 5-line initial capitals. [Herbert 74]

Leaf, 1549 edition of 1537 Matthew Bible, English, Ezra 2:2 - 4:12. Printed by John Daye and William Seres, London. 259 x 164, 7.5" x 11.5" ($55.00)

Leaf, 1549 edition of 1537 Matthew Bible, English, Ezra 2:2 - 4:12. Printed by John Daye and William Seres, London. 259 x 164, 7.5" x 11.5" ($55.00)This work of John Rogers which wields together the best work of Tyndale and Coverdale, is considered to be the real primary version of the modern English Bible. It is a composite consisting of Tyndale’s New Testament of 1535 and as much of the Old Testament as Tyndale had translated before his death (14 books: the Pentateuch and Joshua through 2 Chronicles). The remaining OT books and the Apocrypha were from Coverdale. In this edition, Rogers made extensive changes to the notes of the original 1537 Matthew Bible.

Printed in rather peculiar 10-pt black letter, double columns, 65 lines. References and a few notes in the margins in black letter. Has both 4- and 5-line initial capitals. [Herbert 74]

Leaf, 1539 Taverner Bible, English, Mark 2:19 - 4:38. Printed by John Daye, London. 246 x 162, 7.6" x 11.1" ($45.00)

Leaf, 1539 Taverner Bible, English, Mark 2:19 - 4:38. Printed by John Daye, London. 246 x 162, 7.6" x 11.1" ($45.00)The Taverner Bible was a minor revision of the 1537 Matthew Bible. As a graduate of both Cambridge and Oxford, and a Greek scholar of high repute, Richard Taverner sought to bring more “compression and vividness” to the Biblical text and often substituted a Saxon word for a Latin one. It is this translation that first introduced such words as “parable” and “passover” and other terms still in use. Many marginal notes from the Matthew Bible were omitted and some new comments added. Never officially endorsed by the church, the Taverner Bible had little influence on later revisions and ultimately became more of a curious footnote in history, and a Bible of which very few people are even aware.

Printed in 12-pt black letter, double columns, 68 lines per column. References and a few sidenotes also in black letter. Contents of chapters in smaller 9-pt black letter. Pages are not numbered. [Herbert 45]

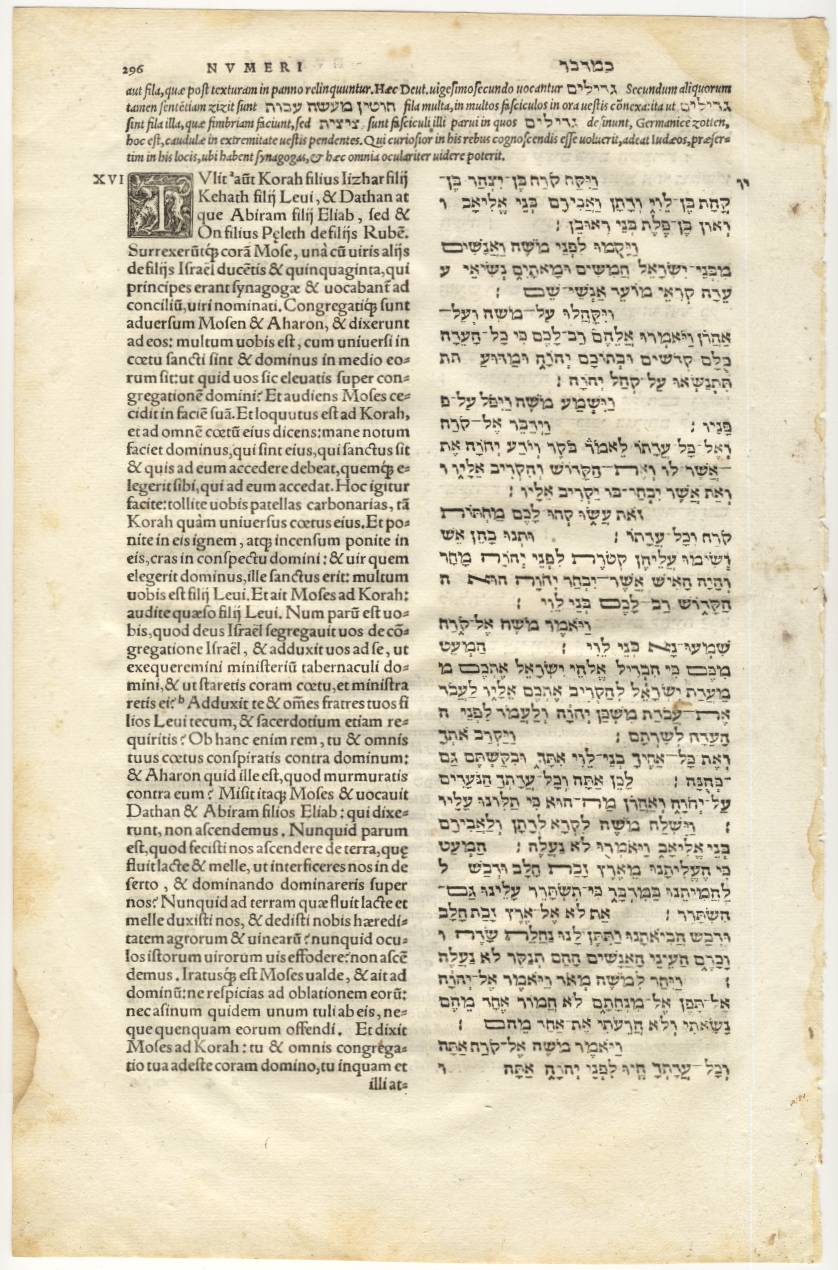

Leaf, 1546 Holy Writings, Hebrew, Numbers 15:31 - 16:16, page 295-296. Printed in Basel. 261 x 152 mm, 8.1" x 12.5" ($23.50)

Leaf, 1546 Holy Writings, Hebrew, Numbers 15:31 - 16:16, page 295-296. Printed in Basel. 261 x 152 mm, 8.1" x 12.5" ($23.50)Title page reads, “Twenty-four books of the Holy Writings [Tanakh or Jewish Bible] copied into the Roman language” by Mikdash Hashem and Otzar Yesha, with a Latin translation and commentary by Sebastian Münster. Although the Complutensian (1517) included Hebrew as one of its four languages, this is one of the first parallel Bibles produced by Jewish scholars. The 24 books of the Tanakh include all 39 books of the Protestant Old Testament, although many are combined in the Jewish Bible, for example, the 12 minor prophets make up just one book, “Trei Asar.”

The column in Hebrew at the left reads from right to left with odd variable indentations while both the column with the Latin translation and the Latin commentary in italics at the top and bottom of the page reads from left to right.

Latin translation is printed in 11-point Roman, 55 lines per column. Hebrew is in approx 12 point. Latin commentary is in 9-pt Roman italics and runs the full width of the page.

Leaf, 1549 Great Wittenberg Bible, Leviticus 16:1 -18:8, High German translation by Martin Luther. Printed by Hans Lufft Press, Wittenberg. 277 x 191, 8.0" x 12.0" ($42.90)

Leaf, 1549 Great Wittenberg Bible, Leviticus 16:1 -18:8, High German translation by Martin Luther. Printed by Hans Lufft Press, Wittenberg. 277 x 191, 8.0" x 12.0" ($42.90)Martin Luther’s Bible is a scholarly translation based on the Hebrew and ancient Greek texts and consultation with numerous scholars. It was written in a vigorous, idiomatic German prose. The New Testament was first published in 1522, but translation of the complete Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments and Apocrypha took 12 more years, and in 1534

was published in a six-part edition. Luther reworked his translation ceaselessly for another 12 years before his death in 1546. Thanks to the then recently invented printing press, the result was widely disseminated and contributed significantly to the development of today’s modern High German language as well as to the Protestant Reformation.

was published in a six-part edition. Luther reworked his translation ceaselessly for another 12 years before his death in 1546. Thanks to the then recently invented printing press, the result was widely disseminated and contributed significantly to the development of today’s modern High German language as well as to the Protestant Reformation.Printed in 12-point black letter, double columns, 62 lines per column with 7-line historiated capitals colored by hand in red, blue, and brown. Note the odd design of the historiated capital V at the left (click on it to see it enlarged).

Leaf, 1549 Great Wittenberg Bible, 2 Samuel 11:11 - 13:13, page 148. High German translation by Martin Luther. Printed by Hans Lufft Press, Wittenberg. 277 x 191, 8.0" x 12.0" ($14.40)

Leaf, 1549 Great Wittenberg Bible, 2 Samuel 11:11 - 13:13, page 148. High German translation by Martin Luther. Printed by Hans Lufft Press, Wittenberg. 277 x 191, 8.0" x 12.0" ($14.40)The translation of the entire Bible into German was published in a six-part edition in 1534, a collaborative effort of Luther and many others. Luther worked on refining the translation up to his death in 1546, indeed he had worked on the edition that was printed that year.

There were 117 original woodcuts included in the 1534 edition issued by the Hans Lufft press in Wittenberg; even more were in later editions. They reflected the recent trend (since 1522) of including artwork to reinforce the textual message. In the following 40 years Lufft printed more than 100,000 copies of the German Bible as well as most of the other works of Luther.

Printed in 12-point black letter, double columns, 62 lines per column with 7-line historiated capitals colored by hand in red, blue, and brown.

Leaf, 1561 Latin Vulgate, Exodus 39:1 - Leviticus 1:17 with small woodcut of Moses with horns. Printed in Antwerp. 284 x 180, 8.7" x 12.9" ($19.00)

Leaf, 1561 Latin Vulgate, Exodus 39:1 - Leviticus 1:17 with small woodcut of Moses with horns. Printed in Antwerp. 284 x 180, 8.7" x 12.9" ($19.00)At Louvain the theological faculty entrusted John Henten with the preparation of a critical edition of the Vulgate in accordance with the wish of the Tridentine Decree. In 1547 he published his revised Vulgate based on Robert Stephan’s edition of 1540. This leaf is most likely from that edition.

Among other things, the Council of Trent (1546) declared the Vulgate to be authentic, meaning “worthy of belief, reliable, credible, truthful, trustworthy, authoritative.” But the Fathers recognized the lack of conformity between the various manuscripts and editions of the Vulgate

and therefore decreed that “Sacred Scripture, and especially this well-known Old Vulgate, shall be published as correctly as possible.” Although appointed in 1561, the commission which was instructed to publish the revision of the Vulgate did nothing for many years so earlier versions such as this one continued in use until 1587.

and therefore decreed that “Sacred Scripture, and especially this well-known Old Vulgate, shall be published as correctly as possible.” Although appointed in 1561, the commission which was instructed to publish the revision of the Vulgate did nothing for many years so earlier versions such as this one continued in use until 1587.The depiction of Moses with horns (left) stems from the description of Moses’ face as “cornuta” (“horned”) in Jerome’s original Latin Vulgate translation of Exodus 34:29.

Printed in Roman type, double columns, 58 lines per column. Small woodcut of Moses and 5-line historiated initial at beginning of Leviticus. A few marginal references.

Leaf, 1561 Bible Interpretation Guide, Latin, with references to the original Hebrew or Greek, page 3. Printed in Antwerp. 286 x 186, 8.7" x 13.0" ($18.42)

Leaf, 1561 Bible Interpretation Guide, Latin, with references to the original Hebrew or Greek, page 3. Printed in Antwerp. 286 x 186, 8.7" x 13.0" ($18.42)This Interpretation Guide is alphabetical in Latin and has names of men, women, rulers, peoples, idols, cities, rivers, mountains, places, and other proper names. Includes interpretation and description of each entry in Latin along with the scripture reference. Side column shows the word in Hebrew or Greek as it originally appeared. This page includes Latin words beginning in AH, AI, AL, AM, and the start of AN.

Printed in 10-point Roman type, double columns, 77 lines per column. Outer columns show the word in the original language, Hebrew or Greek. Three wormholes at bottom left.

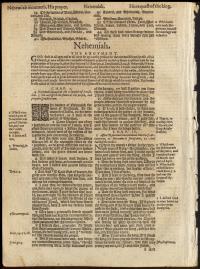

Leaf, 1562 Great Bible, English, 1 Maccabees 8:27 - 9:65. Printed by Richard Harrison, London. 284 x 185, 8.1" x 11.7" ($10.00)

Leaf, 1562 Great Bible, English, 1 Maccabees 8:27 - 9:65. Printed by Richard Harrison, London. 284 x 185, 8.1" x 11.7" ($10.00)In 1539, Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, hired Myles Coverdale at the behest of King Henry VIII to publish a Bible. It became the first English Bible authorized for public use, as it was distributed to every church, chained to the pulpit “in a convenient place so parishioners may most commodiously resort to the same and read it.” It became known as the Great Bible due to its large page size over 14 inches tall, although quarto-size ones like this one were also printed. It was withdrawn when Mary Tudor became queen 1553 and attempted to reinstate Catholicism in England. It was once again approved in 1559 after the accession of Elizabeth I to the throne. The last of over 30 editions of the Great Bible appeared in 1569.

Printed in black letter with sidenotes in Roman font, double columns, 58 lines per column, 6-line capital hand colored red. No page numbers. For this edition, Harrison was fined for printing without a license. [Herbert 117]

Leaf, 1562 La Sacra Biblia, Vernacular Italian, Acts 7:11 - 9:5. Printed by Francesco Durone, Geneva, Switzerland. 230 x 147, 6.5” x 9.5” ($7.00)

Leaf, 1562 La Sacra Biblia, Vernacular Italian, Acts 7:11 - 9:5. Printed by Francesco Durone, Geneva, Switzerland. 230 x 147, 6.5” x 9.5” ($7.00)This Italian language translation of the Scriptures is typical of late 16th century printings of the Bible. Double columns of text are presented in the now-standard Roman type face, with commentary and side notes in smaller sized fonts. Page is representative of the many translations of the Bible into the vernacular, or common language of the people, which appeared after the invention of printing. These new books were widely disseminated across the Christian world as a result of this dynamic new technology and made the Scriptures, heretofore accessible only to those educated in Latin, available to all the faithful. However, in 1559, Pope Paul IV, attempting to abolish the spread of “heresies,” i.e., Protestantism, forbade further vernacular editions of the Scriptures. This Bible printed in 1562 in Switzerland, far from Papal control, was the last Italian Bible printed until 1607.

Printed in small 8-pt Roman font, two columns, 66 lines per column, sidenotes in tiny 5-pt type, chapter summaries in 6-pt italics. (D&M, Historical Catalogue of the Bible, no. 5592)

Leaf, 1565 Greek and Latin New Testament by Theodore Beza, Luke 2:17-30. Printed in Geneva. 282 x 174, 9.2" x 13.8" ($42.00)

Leaf, 1565 Greek and Latin New Testament by Theodore Beza, Luke 2:17-30. Printed in Geneva. 282 x 174, 9.2" x 13.8" ($42.00)In this New Testament, the left column is Greek, the middle column is Beza’s Latin translation of the Greek, and the right column is Jerome’s Latin Vulgate. This is the earliest of Beza’s editions of the Greek Testament and is generally known as Beza’s first major edition.

Beza was indebted to the previous edition of the eminent Robert Estienne, which was itself based in great measure upon one of the editions of Erasmus. Beza’s labors in this direction were exceedingly helpful to those who came after. The same thing may be asserted of his Latin version (published over 100 times) and of the copious notes with which it was accompanied.

Folio page printed in 3 columns of 9 to 11-point type with extensive 8-pt footnotes (often more than half a page). [Darlow and Moule, no. 4629]

Leaf, 1566 Missale Romanum, Latin, Mass Celebrated For Christian Martyrs. Printed by Giovanni Varisco, Venice. 8.7" x 12.0" ($25.00)

Leaf, 1566 Missale Romanum, Latin, Mass Celebrated For Christian Martyrs. Printed by Giovanni Varisco, Venice. 8.7" x 12.0" ($25.00)The Missale Romanum (Roman Masses) contains the text of the Tridentine Calendar of saints to be honoured each year. The Tridentine Calendar is the official liturgy of the Roman Rite as reformed by Pope Pius V. This particular leaf contains the text for the mass celebrated for two or more martyrs. The 1566 edition in this size is quite scarce.

Giovanni Varisco and his family members were wealthy Venetian printers with bookshops in Rome and Naples.

Printed in black letter, double columns, 41 lines per column. Headings and key words are in red ink with generic woodcuts in black ink for capital letters as well as to depict various saints, apostles and Biblical scenes.

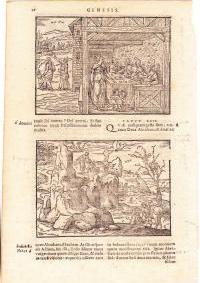

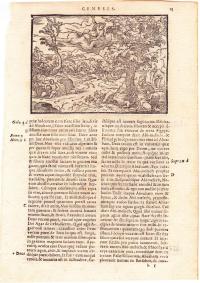

Leaf, 1567 Latin Vulgate, Genesis 21:12 - 22:3, with three large illustrations. Published by Guglielmo Rovillium, Lyon. 157 x 111, 4.75" x 7.5" ($20.00)

Leaf, 1567 Latin Vulgate, Genesis 21:12 - 22:3, with three large illustrations. Published by Guglielmo Rovillium, Lyon. 157 x 111, 4.75" x 7.5" ($20.00)One of the many printings of a corrected Vulgate. Text is from the middle part of Genesis. The woodcuts are said to be by Pierre Eskrich (1530-1590) and Thomas Arande, both being inspired by Bernard Salomon. However, a 1913 catalogue from Leo Olschki, “Livres a figures des XV et XVI siecle,” attributes the woodcuts to Jean Moni, inspired by Bernard Salomon. The woodcuts are: (1) Sarah by a tree watching Hagar’s son playing (Gensis 21:9), with God or an angel watching above, (2) Abraham casting out Hagar and her son (Gen 21:14) (note the two little children fighting, in the bottom center!), and (3) Abraham preparing to sacrifice his son, Isaac, with God or an angel watching from above with Abraham’s two servants at the bottom right (Gen 22:3).

Printed in small 7-pt Roman font, two columns, 56 lines per full column, sidenotes in italics

Leaf, 1572 Bishops Bible, English, Numbers 20:18 - 21:31 with engraving of Moses with horns and the bronze serpent. Printed by Richard Jugge, London. 349 x 232, 10.4" x 14.2" ($45.00)

Leaf, 1572 Bishops Bible, English, Numbers 20:18 - 21:31 with engraving of Moses with horns and the bronze serpent. Printed by Richard Jugge, London. 349 x 232, 10.4" x 14.2" ($45.00)In 1559, Queen Elizabeth ordered that a Bible be placed in every parish church for which purpose the Great Bible was reprinted. But Archbishop of Canterbury Matthew Parker wanted a new translation more suitable for reading aloud in church. So in 1566 he assigned sections of the Great Bible to teams of revisers, most of them bishops. The result was a conservative and dignified translation that avoided harsh comments on the Roman Catholic Church. It went through 20 editions in 42 years and served as the official basis of the King James Version.

The depiction of a horned Moses stems from the description of Moses’ face as “cornuta” (“horned”) in the Latin Vulgate translation of Exodus 34:29 in which Moses returns to the people after receiving the commandments for the second time. The Douay-Rheims Bible translates the Vulgate into English as, “And when Moses came down from the mount Sinai, he held the two tables of the testimony, and he knew not that his face was horned from the conversation of the Lord.” This was Jerome’s effort to faithfully translate the difficult, original Hebrew Masoretic text, which uses the term, karan (based on the root, keren, which often means “horn”); the term is now interpreted to mean shining, radiant, or emitting rays.

The depiction of a horned Moses stems from the description of Moses’ face as “cornuta” (“horned”) in the Latin Vulgate translation of Exodus 34:29 in which Moses returns to the people after receiving the commandments for the second time. The Douay-Rheims Bible translates the Vulgate into English as, “And when Moses came down from the mount Sinai, he held the two tables of the testimony, and he knew not that his face was horned from the conversation of the Lord.” This was Jerome’s effort to faithfully translate the difficult, original Hebrew Masoretic text, which uses the term, karan (based on the root, keren, which often means “horn”); the term is now interpreted to mean shining, radiant, or emitting rays.Printed in large 20-pt black letter, double columns, 57 lines per column, 7-line capital with minimal sidenotes in 11-pt Roman font. No page numbers. [Herbert 132]

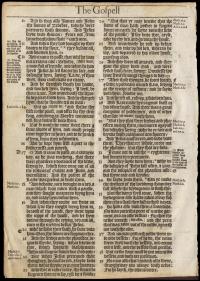

Leaf, 1572 Bishops Bible, Luke 4:18 - 5:39. Printed by Richard Jugge, London. 349 x 232, 9.9" x 14.0" ($12.24)

Leaf, 1572 Bishops Bible, Luke 4:18 - 5:39. Printed by Richard Jugge, London. 349 x 232, 9.9" x 14.0" ($12.24)This is the first edition of the Bishop’s Bible, a revision of the Great Bible, undertaken by Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury. The work was carried out in several sections, which vary considerably in value. In correcting the Great Bible, both the Greek and Hebrew originals were consulted as well as Castalio’s Latin version of 1551. The alterations in the NT show original and vigorous scholarship. As in the Geneva Bible of 1560, verse numbers are printed by each verse, but the old division letters (A, B, C...) are also retained.

An old account book of St. John’s College, Cambridge shows a price for this edition of 27s 8d. (This may sound cheap, but actually was about 8-9 month’s wages at the time.)

An old account book of St. John’s College, Cambridge shows a price for this edition of 27s 8d. (This may sound cheap, but actually was about 8-9 month’s wages at the time.)A curious note appears at Psalm 65:9, “Ophir is thought to be the Ilande in the west coast, of late founde by Christopher Columbo: fro whence at this day is brought most fine golde.” (In the Bible, “Ophir” is a wealthy port region.)

Printed in large 20-pt black letter, double columns, 57 lines per column, 7-line colored capital with minimal sidenotes in 11-pt Roman font. No page numbers. [Herbert 132]

Leaf, 1575? Geneva Bible, Psalm 120:2 - 128:3, page 280. 193 x 119, Printed by Iohn Crispin, Geneva. 5.5" x 8.0" ($8.29)

Leaf, 1575? Geneva Bible, Psalm 120:2 - 128:3, page 280. 193 x 119, Printed by Iohn Crispin, Geneva. 5.5" x 8.0" ($8.29)The Geneva is the earliest English Bible printed in Roman type with verse divisions. Translated by W. Whittingham, Anthony Gilby, Thomas Sampson, and perhaps others who fled to Geneva during the reign of Queen Mary. Whittingham’s NT is based on Tyndale’s, compared with the Great Bible, and also influenced by Beza’s Latin translation. The OT is based mainly on the Great Bible. The influence of Olivetan’s French Bible is also evident in that the “Arguments” to Job and the Psalms are translated almost word for word from the French edition of 1559.

A Bible with these page dimensions (type area of 193 x 119 mm) and type size (7 point Roman) is not listed in the Herbert catalog. The closest is a 1587 Bible by Christopher Barker with type area 195 x 129, a full centimeter wider. The seller claimed this was a 1575 edition, which seems unlikely, but lacking better information, we’ll have to leave it at that.

Duodecimo size although generally called octavo. Printed in small 7-point Roman type, double columns, 63 lines per column. “Arguments” of each psalm in italics, extensive sidenotes in tiny 5-pt Roman type. Red rules added after printing for wealthy purchasers. [No reference]

Leaf, 1576 Tract on the Church, Latin, from Gerard Jansen, Decem de Ecclesia Tractatus. Printed by Martin Cholinus, Cologne, Germany. 159 x 99, 5.3” x 7.7” ($6.50)

Leaf, 1576 Tract on the Church, Latin, from Gerard Jansen, Decem de Ecclesia Tractatus. Printed by Martin Cholinus, Cologne, Germany. 159 x 99, 5.3” x 7.7” ($6.50)This interesting work of “ten tracts on the Church, necessitated by these troubled times” asserts the primacy of the Roman Church then under threat by the Protestant Reformation, explaining away its huge wealth and civil power; tracing its succession from Peter; its Scriptural legitimacy, etc. The author, Cornelius Jensen the Elder (1510 - 1576), was one of the most distinguished Biblical exegetes (commentators) of his time. In his works he insisted on the literal interpretation of Scriptures, as against the mystical interpretation of some of his predecessors; he also emphasized the importance of the original text. His son became the founder of Jansenism.

Printed in Roman 12-pt type, single column, 35 lines, 3-line initial capital.

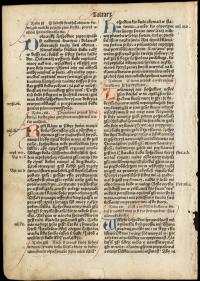

Leaf, c. 1577 Commentary by Martin Luther (1534-37) on Galatians 1:4. Folio 23. Translated into English 1577. 164 x 114, 5.3" x 7.4" ($7.00)

Leaf, c. 1577 Commentary by Martin Luther (1534-37) on Galatians 1:4. Folio 23. Translated into English 1577. 164 x 114, 5.3" x 7.4" ($7.00)Luther’s Commentary was based on a course of lectures which he delivered in 1531 at the University of Wittenberg, where for over 30 years he was Professor of Biblical Exegesis. Notes from these lectures were first published in Latin in 1534 followed by a revised version in 1538. Just over 30 years later, in 1575, the first English edition was published, the translation being based on the second Latin edition. In 1577 it was “diligently revised, corrected, and newly imprinted again.”

Printed in black letter, single column, 39 lines, with sidenotes in 7-pt Roman type.

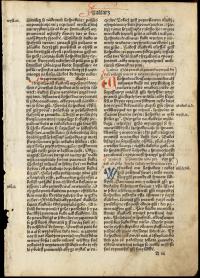

Leaf, c. 1577 Commentary by Martin Luther (1534-37) on Galatians 4:13-14. Folio 209. Translated into English 1577. 164 x 114, 5.3" x 7.4" ($7.00)

Leaf, c. 1577 Commentary by Martin Luther (1534-37) on Galatians 4:13-14. Folio 209. Translated into English 1577. 164 x 114, 5.3" x 7.4" ($7.00)The Epistle to the Galatians was a favorite of Luther’s. He called it “my own Epistle, to which I have plighted my troth. It is my Katie von Bora.” He found in it a source of strength for his own faith and life, and an armory of weapons for his reforming work. He had twice expounded it previously: in 1519, when he largely depended on St. Jerome and Erasmus for his exegesis, and in 1523, when he departed from them both. In the present work he frequently expresses his dissent from St. Jerome, and occasionally takes issue with Erasmus. Luther came to think very little of his earlier commentaries and in 1531 he seems to have decided to lecture again on the Epistle because he felt that the centrality of the doctrine of justification had been somewhat obscured during the controversies of the preceding years.

Printed in black letter, single column, 39 lines, with sidenotes in 7-pt Roman type.

Leaf, 1578 Bishops Bible, English, Daniel 9:24 - 11:18, page 135. Printed by Christopher Barker, London. 312 x 203, 8.9" x 13.2" ($6.00)

Leaf, 1578 Bishops Bible, English, Daniel 9:24 - 11:18, page 135. Printed by Christopher Barker, London. 312 x 203, 8.9" x 13.2" ($6.00)The Bishops Bible was a revision of the Great Bible ordered by Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury. The translators were instructed to depart from the Great Bible only to correct inaccuracies, clean up offensive language, or mark dull passages so that readers could bypass them. Through entirely reset by C. Barker, this edition closely resembles the 1574 folio printing by R. Jugge.

Printed in large 16-pt black letter, double columns, 63 lines per column, extensive sidenotes in 9-pt black letter. Trimmed extremely close to text on right; original page was 9¼" wide. [Herbert 155]

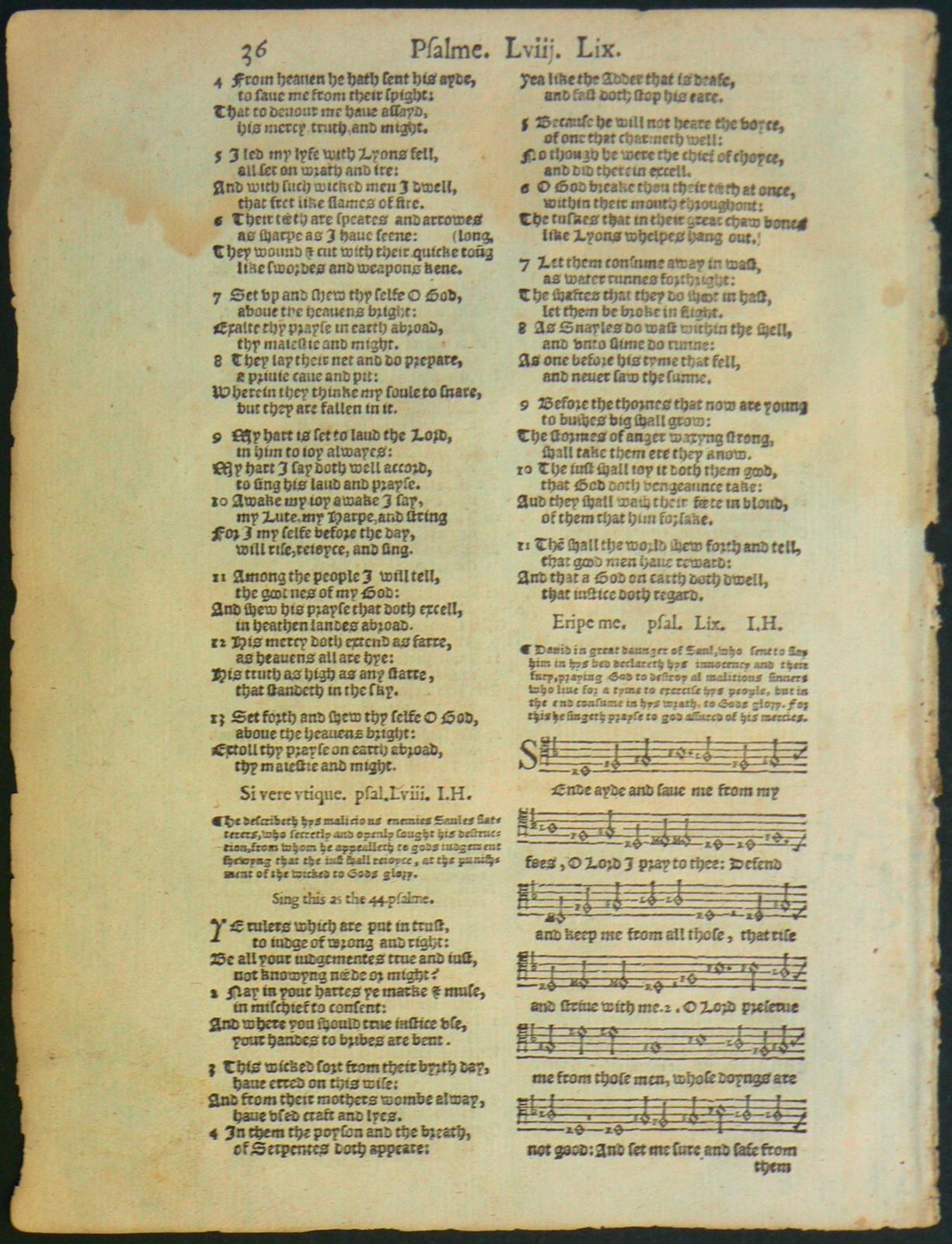

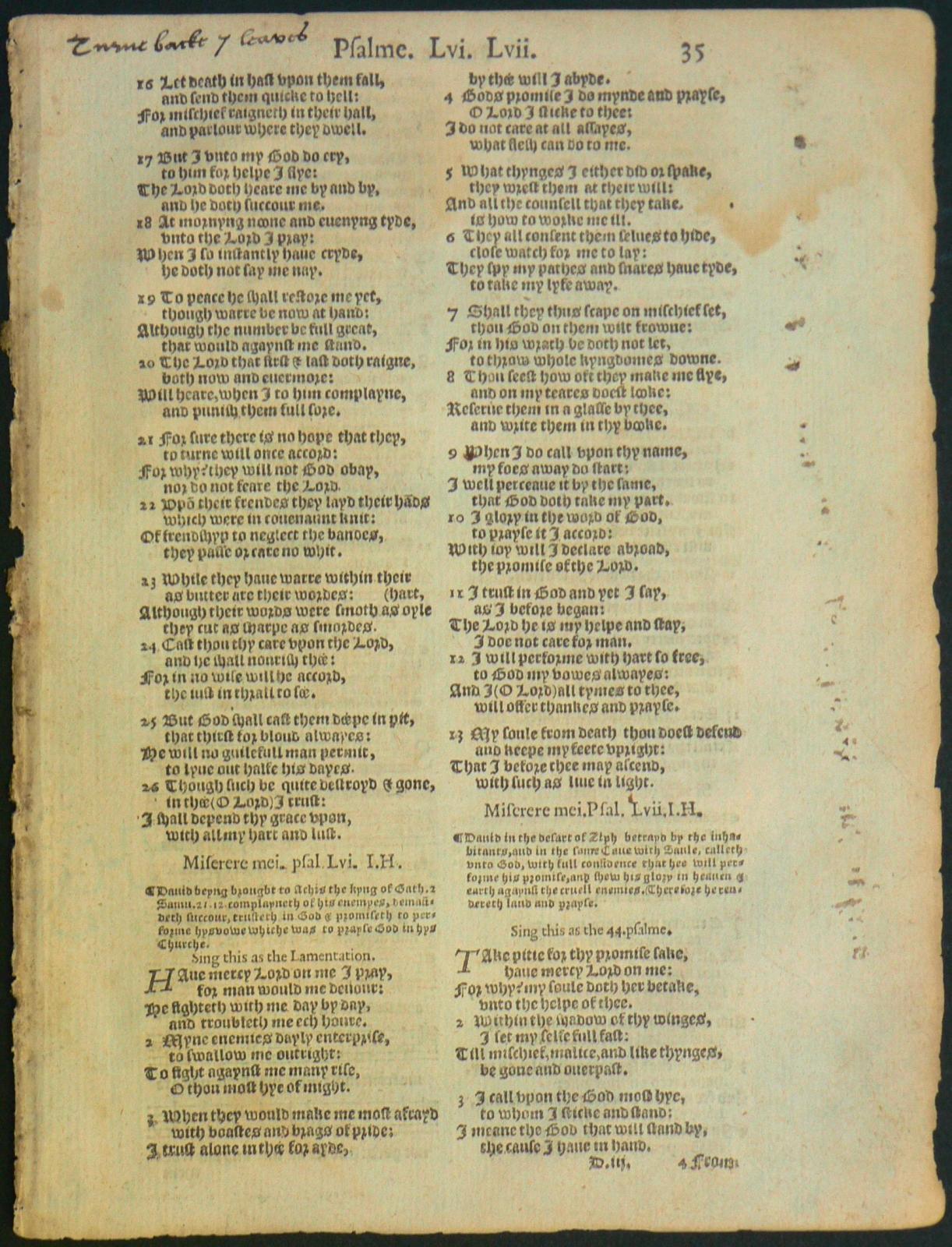

Leaf, 1580 The Whole Book of Psalms (Psalter) by T. Sterneholde, I. Hopkins, &c., English, Psalm 55:16 - 59:1, page 35-36 with music stanza. Printed by John Daye, London. 186 x 100, 6.1" x 8.0" ($4.00)

Leaf, 1580 The Whole Book of Psalms (Psalter) by T. Sterneholde, I. Hopkins, &c., English, Psalm 55:16 - 59:1, page 35-36 with music stanza. Printed by John Daye, London. 186 x 100, 6.1" x 8.0" ($4.00)The Psalms in this psalter have been reworded so they rhyme in English and have the same number of syllables in each line for singing. Psalm 59 has a musical stanza for the first two verses.

Printed in 9-pt black letter, double columns, 67 lines. Notes about several psalms in tiny 6-pt black letter.

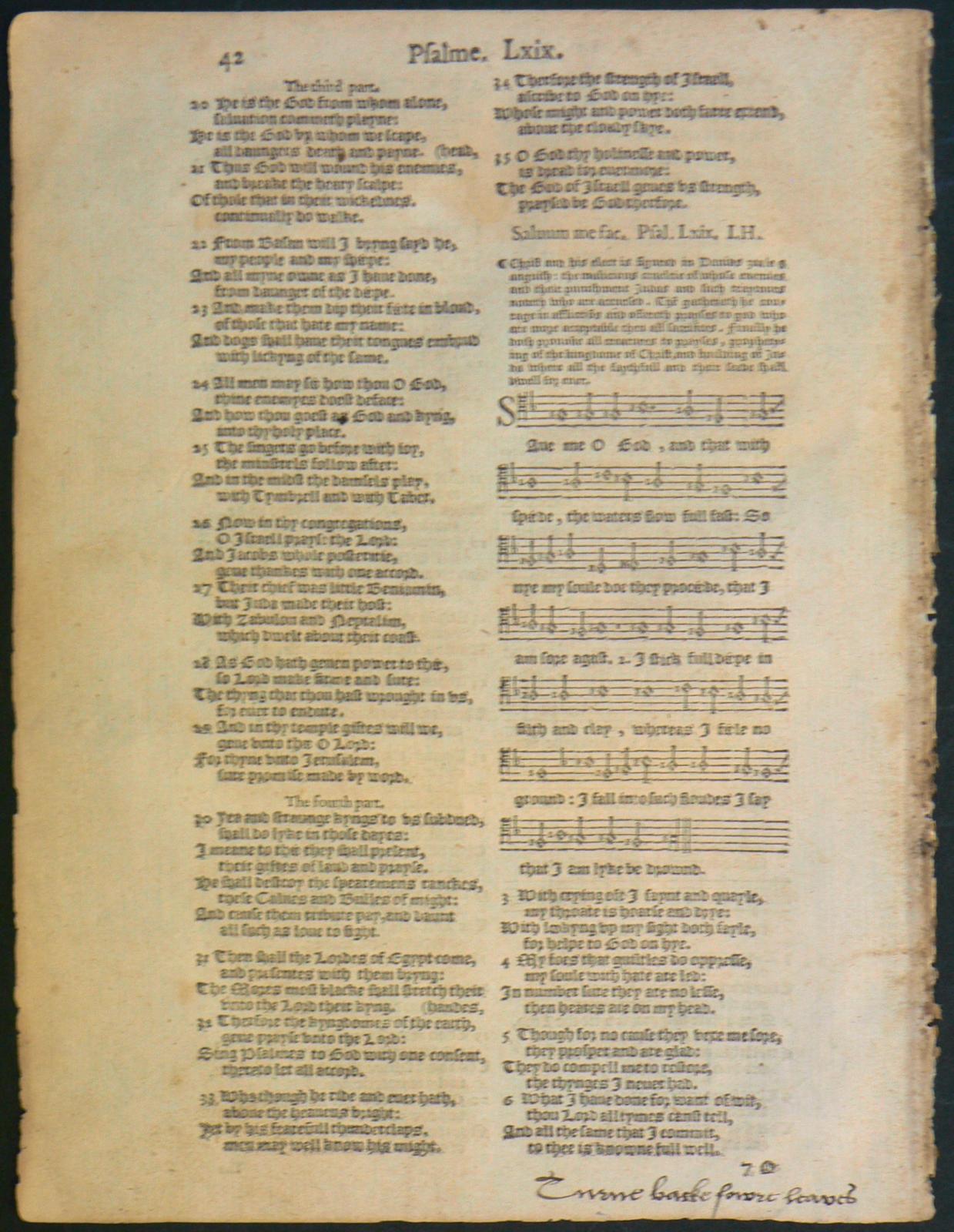

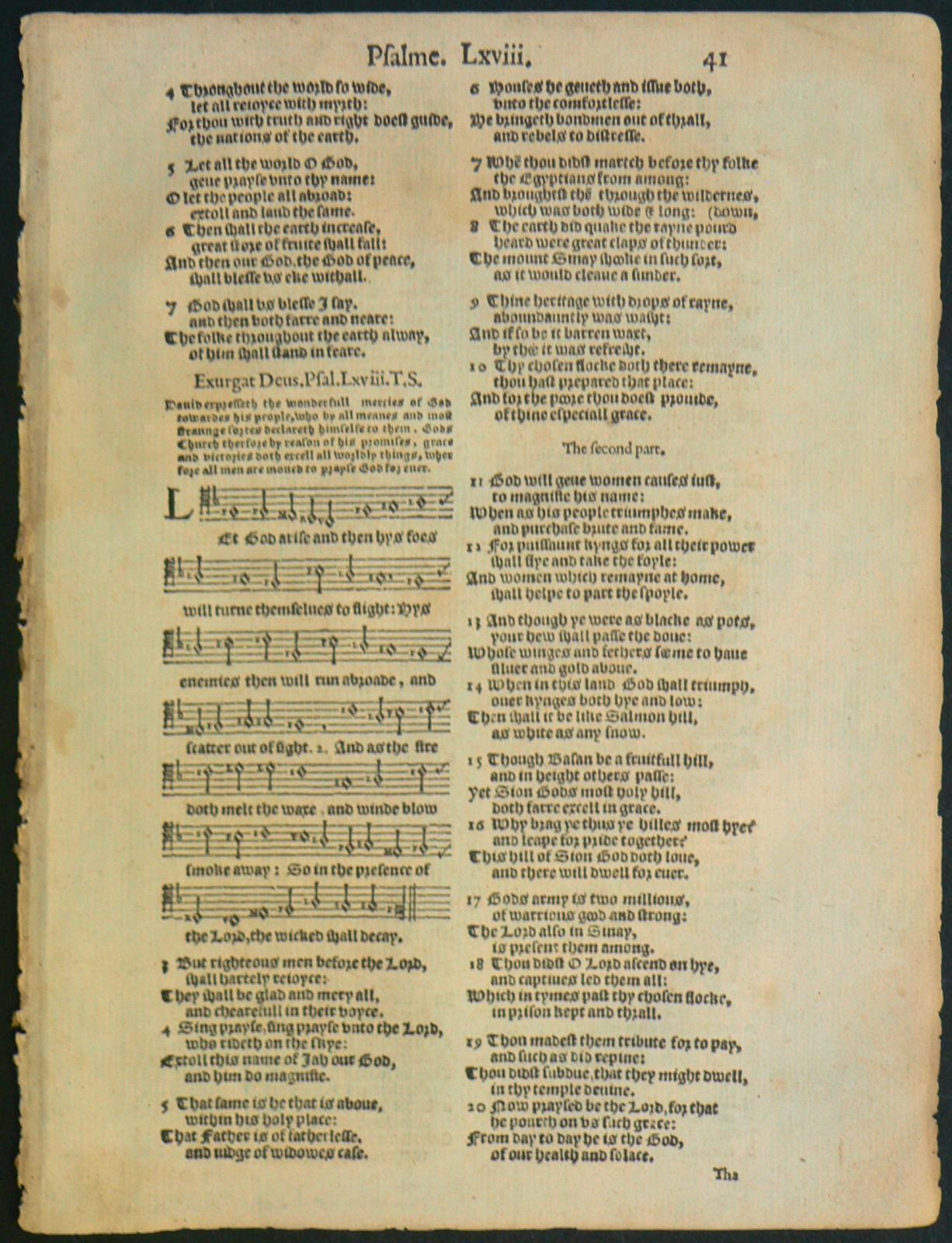

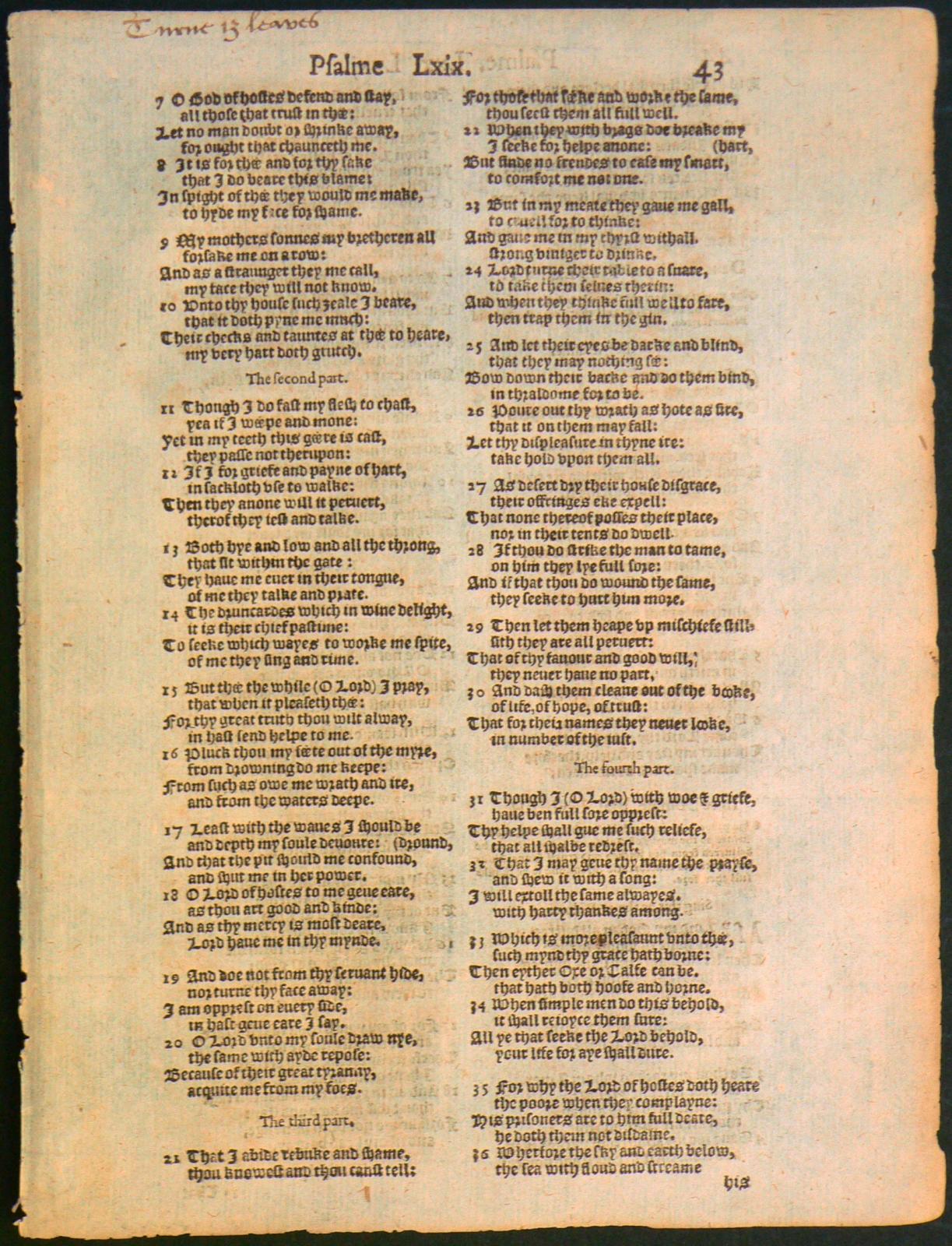

Leaf, 1580 The Whole Book of Psalms (Psalter) by T. Sterneholde, I. Hopkins, &c., English, Psalm 67:4 - 69:6, page 41-42 with music stanza. Printed by John Daye, London. 186 x 100, 6.1" x 8.0" ($4.00)

Leaf, 1580 The Whole Book of Psalms (Psalter) by T. Sterneholde, I. Hopkins, &c., English, Psalm 67:4 - 69:6, page 41-42 with music stanza. Printed by John Daye, London. 186 x 100, 6.1" x 8.0" ($4.00)The Psalms are “set forth to be sung in all Churches, of all the people together before and after Morning and Evening prayer; as also before and after Sermons and moreover in private homes, for their solace and comfort.” Psalms 68 and 69 have a musical stanzas for the first two verses of each psalm.

Printed in 9-pt black letter, double columns, 67 lines. Notes in tiny 6-pt black letter.

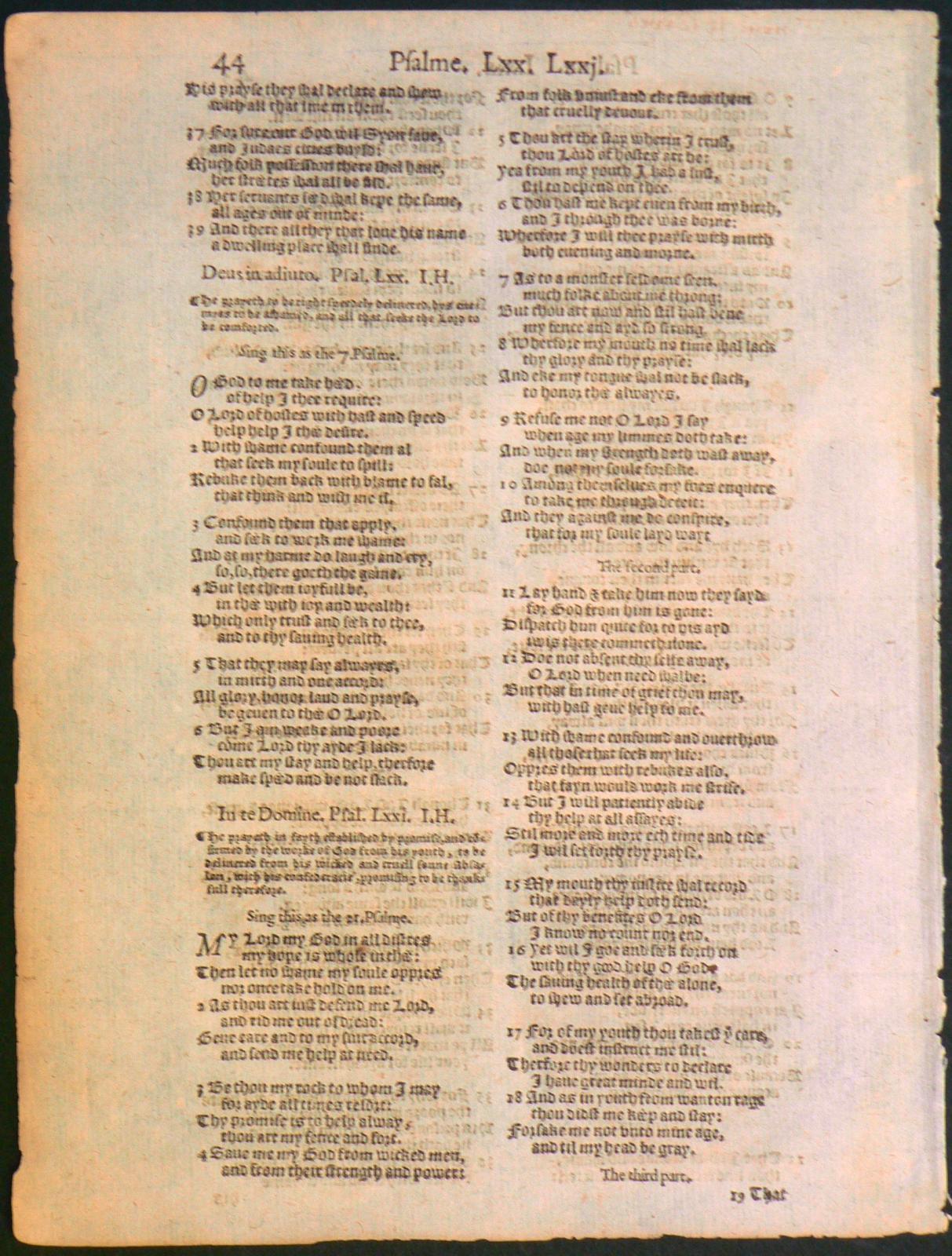

Leaf, 1580 The Whole Book of Psalms (Psalter) by T. Sterneholde, I. Hopkins, &c., English, Psalm 69:7 - 71:18, page 43-44. Printed by John Daye, London. 186 x 100, 6.1" x 8.0" ($3.00)

Leaf, 1580 The Whole Book of Psalms (Psalter) by T. Sterneholde, I. Hopkins, &c., English, Psalm 69:7 - 71:18, page 43-44. Printed by John Daye, London. 186 x 100, 6.1" x 8.0" ($3.00)The title page notes the Psalms are “collected into English meter by T. Sterneholde, I. Hopkins and others, confered with the Ebrue, with apt Notes to sing them withall.”

Printed in 9-pt black letter, double columns, 67 lines. Notes about Psalms 70 and 71 in tiny 6-pt black letter.

Leaf, 1583 Geneva Bible, English, 2 Samuel 5:4 - 7:9. Printed by Christopher Barker, London. 354 x 225, 10.8" x 15.7" ($25.00)

Leaf, 1583 Geneva Bible, English, 2 Samuel 5:4 - 7:9. Printed by Christopher Barker, London. 354 x 225, 10.8" x 15.7" ($25.00)The Geneva Bible first appeared in quarto format in 1560, the work of reformers who had fled to Geneva to escape persecution in England during the reign of Queen Mary. Geneva was the stronghold of Calvinism, where the translators had access to the most advanced Biblical scholarship of the day. Title page notes: “Translated according to the Ebrew and Greeke, with most profitable Annotations.” It was the first English Bible in which chapters were divided into verses. An important feature was the marginal notes, often of a puritanical character. King James I took personal exception to these notes, with their bitterness toward the Church of England, and his dislike of them is partly responsible for the later translation that bears his name. Though never officially adopted, the Geneva version was the standard English translation for three generations, familiar to Shakespeare, Bunyan, and the soldiers of the Civil War. Thus it is of cardinal importance for its influence on English literature, language, and thought.

This edition is the most sumptuous printing of the Geneva Bible, folio size, in large 20-pt black letter, double columns, 59 lines, sidenotes in12-pt black letter. While there were 144 editions of this very popular Bible, none approaches this beautiful edition in sheer size and quality of execution. [Herbert 178]

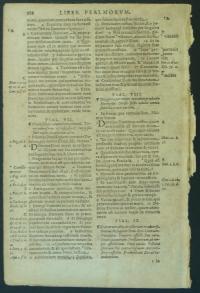

Leaf, 1583 Biblia Sacra, Latin, Psalms 136:14 - 141:3. Printed by Christopher Plantin at Antwerp, Holland. 349 x 240, 10.7" x 16.1" ($10.00)

Leaf, 1583 Biblia Sacra, Latin, Psalms 136:14 - 141:3. Printed by Christopher Plantin at Antwerp, Holland. 349 x 240, 10.7" x 16.1" ($10.00)This famous edition of the Louvain Bible was used by Cardinals and scholars in the revision of the Latin Vulgate text ordered by Pope Sixtus V in 1589.

This remarkable large folio Bible is among the finest products of the press of Plantin, the outstanding scholar-printer of the age. It utilizes a superb Roman typeface designed by Pieter Huys. Double column, 50 lines of Latin text in large 18-pt Roman type with small 8-pt sidenotes.

Leaf, 1584 Biblia Hebraica. Eorundum Latina Interpretatio Xantis Pagnini.[The Hebrew Bible, with Latin Text after Pagnini]. Ezekiel 42:6 - 44:7, page 141-42. Printed by Christopher Plantin, Antwerp. 303 x 187, 8.5" x 13.2" ($12.50)

Leaf, 1584 Biblia Hebraica. Eorundum Latina Interpretatio Xantis Pagnini.[The Hebrew Bible, with Latin Text after Pagnini]. Ezekiel 42:6 - 44:7, page 141-42. Printed by Christopher Plantin, Antwerp. 303 x 187, 8.5" x 13.2" ($12.50)Bible is two parts bound in one. Edited by Benedictus Arias Montano. Hebrew text of the Old Testament and Greek text of the New Testament and Apocrypha, each with an interlinear Latin translation (reading, like the Hebrew, from right to left) by Santes Pagnini.

This Bible is based on Plantin’s “polyglot Bible” of 1573 which, with the patronage of King Philip II of Spain, became the standard for the original texts. The printing dynasty he founded flourished well into the 17th century, and the original workshop today survives as the Plantin-Moretus Museum.

Double columns of Hebrew text with sidenotes, 36 lines, interlinear Latin text in a small 7-pt Roman font above the Hebrew. [Darlow & Moule 5106]

Leaf, 1584 Novum Testamentum Graecum. Cum Vulgata Interpretatione Latina [The New Testament in Greek, with the Latin Vulgate Translation], Matthew 16:23 - 19:16. Printed by Christophe Plantin, Antwerp. 298 x 187, 8.5" x 13.2" $10.00)

Leaf, 1584 Novum Testamentum Graecum. Cum Vulgata Interpretatione Latina [The New Testament in Greek, with the Latin Vulgate Translation], Matthew 16:23 - 19:16. Printed by Christophe Plantin, Antwerp. 298 x 187, 8.5" x 13.2" $10.00)This Bible was prepared under the supervision of the Biblical scholar Benedictus Arias Montanus, and offers the best known version of the text of the New Testament canon. Necessary Latin departures from the Greek word and word interpretations appear in the margins. Verse numbers are in the opposite margins.

Double columns of Greek text with sidenotes, 46 lines, interlinear Latin text in a minuscule 5-pt Roman font above the Greek. [Darlow & Moule 4645]

Leaf, 1585 Geneva Bible, English, 2 Kings 17:16 - 18:34, page 153-54. Printed by Christopher Barker, London. 200 x 139, 6.2" x 8.3" ($10.00)

Leaf, 1585 Geneva Bible, English, 2 Kings 17:16 - 18:34, page 153-54. Printed by Christopher Barker, London. 200 x 139, 6.2" x 8.3" ($10.00)In the 1550's, the Church at Geneva, Switzerland, was very sympathetic to reformer refugees such as Myles Coverdale, John Foxe, Thomas Sampson, and William Whittingham. There, with the encouragement of the great theologians John Calvin and John Knox, the Church of Geneva determined to produce a Bible that would educate their families while they continued in exile. The New Testament was completed in 1557, and the complete Bible, first published in 1560, became known as the Geneva Bible. The Geneva Bible is noted for a number of innovative features, chief among them its groundbreaking inclusion of verse numbers throughout the biblical text.

Printed in 9-point black letter rather than Roman type frequently used for Geneva Bibles, marginal notes in small 7-pt Roman type, double columns, 71 lines per column. This is a close reprint of the 1580 edition [Herbert 165], which became a favorite for reprinting. [Herbert 187]

Leaf, 1587 Biblia Hebraicorum. [The Hebrew Bible, Part III]. Ezekiel 23:16-29, 23:30-44. Printed by Johannes Saxonus, Hamburg, Germany. 324 x 195, 9.6" x 15" ($12.50)

Leaf, 1587 Biblia Hebraicorum. [The Hebrew Bible, Part III]. Ezekiel 23:16-29, 23:30-44. Printed by Johannes Saxonus, Hamburg, Germany. 324 x 195, 9.6" x 15" ($12.50)From the First Edition Elias Hutter’s magnificent multi-volume printing of the Hebrew Bible. Hutter’s concern was neither for correctness of text nor beauty of typography, though he succeeded in both. His was a more practical, scholarly mission, to make the Hebrew Bible more readily accessible to the student. He therefore used two forms of type: a solid letter for the root and a hollow letter for the prefixes and suffixes, which makes the page aesthetically pleasing with its subtle shading, vowel points and flourishes. Hebrew language text set in single column of large font Hebrew type. [Darlow & Moule 5108]

Leaf, 1587? Greek and Latin (2 versions) Bible with extensive Latin commentary, Hebrews 11:2-12, page 397-98. 282 x 159, 8.7" x 13.7" ($14.00)